6 Liver

6.1 Preamble

Liver transplantation is a highly successful treatment for advanced liver disease, both in terms of extending and improving quality of life. The demand for liver transplantation and the shortfall in the number of donor organs available means that it is not currently possible to transplant every patient who might individually derive benefit from the procedure. This imbalance means that if every patient who stood to benefit from liver transplantation— even if only marginally—was placed on the waiting list then the list, and therefore waiting times, would become so long that most patients would die before ever being offered a transplant. In this scenario, many patients receiving a liver transplant would have their lives extended only marginally, while others—for whom liver transplantation might extend their lives by decades—would die on the waiting list. Therefore, liver transplantation is offered only to patients whose liver disease is of such a severity that their risk of dying within two years without a transplant exceeds 50%.

At the same time, it is necessary to strike a balance between maximising access to liver transplantation for those who would die without it and achieving the best possible outcome from each transplant. This balance is the single most difficult issue in liver transplantation because there is no “maintenance” treatment equivalent to renal dialysis, and thus there is only a finite time that patients can wait for a liver transplant. For the past 20 years, it has been agreed by the liver transplant units in Australia and New Zealand that eligibility for entry to the liver transplant waiting list should be set at an expectation that a patient has a greater than 50% likelihood of surviving at least five years after liver transplantation; this aligns with international benchmarks. In 2021, five-year patient survival among liver transplant recipients in Australia and New Zealand was 84%, while waiting list mortality (died on waiting list or within one year of delisting) was approximately 5%.11 33rd ANZLITR Registry Report - 2021. Michael Fink and Mandy Byrne. Australia and New Zealand Liver and Intestinal Transplant Registry, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. ×

There are arguments for and against setting such minimal listing criteria or “survivorship thresholds”; this difficult area—of balancing utility versus individual equity—is informed by the Ethical Guidelines.2 It should also be appreciated that there are some patients with liver disease who would not benefit from liver transplantation. Liver transplantation is a massive surgical procedure, and the associated risks can outweigh the risks associated with the natural history of the underlying liver disease. Minimal listing criteria are therefore needed in order to prevent patients with less severe liver disease from being offered a liver transplant that would be riskier than continuing to live with their liver disease.2 National Health and Medical Research Council (2025). Ethical guidelines for cell, tissue and organ donation and transplantation in Australia. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council. ×

Additional complexity arises because the manifestations of liver disease are varied. There is no single indicator of liver dysfunction (unlike, by comparison, serum creatinine level in chronic kidney disease) that allows transplant units to track the decline of patients with liver disease, or to compare the severity of liver disease between patients (although the MELD score comes closer than many other systems; see below). Furthermore, not all patients in need of a liver transplant will die from liver failure without one. A common example is patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)—these patients have underlying chronic liver disease, but their survival is usually determined by the progression of the cancer rather than the failure of liver function. The particular relationship between HCC and eligibility for liver transplantation is covered in Section 6.2.3. Thus, it is difficult to “rank” the urgency of the need for liver transplant for patients on the waiting list. This is discussed in more detail in Section 6.3.

In the case of liver allocation, unlike other forms of solid organ transplantation, tissue matching beyond simple ABO blood group compatibility has little impact on transplant outcomes. However, there are other factors that are very important considerations in liver allocation, from technical factors such as size (a liver retrieved from a very large donor may not fit in a small transplant recipient and conversely a small liver may not provide adequate function in a large recipient), to how well the graft is likely to work initially (very sick recipients do not tolerate donor livers that have impaired function immediately after transplant), to complex logistical issues related to organ transportation (long preservation times resulting from transporting a donor liver over a great distance can have serious negative effects on the transplant outcome). The general principle is that a donor liver is allocated to the sickest patient for whom the liver is suitable; if the liver is of an incompatible blood type or there is a size mismatch then it would not be helpful to transplant it into the sickest patient on the waiting list—in this case it would be offered to the next sickest patient for whom there would be an acceptable chance of successful transplantation with that organ. In this way, allocation decisions are made to enable the best outcome from every transplant.

Most deceased donor livers are allocated to patients with chronic liver disease on a state-based allocation system. However, there are situations where the liver can suddenly fail without warning, such as in acute Hepatitis B infection or paracetamol poisoning – in these situations patients can present to hospital and die within days. Additionally, children with a rare form of liver cancer called hepatoblastoma need access to liver transplantation in a time-sensitive manner (liver transplantation needs to occur rapidly after chemotherapy treatment is completed to secure the best chance of cure). The circumstances of urgent liver transplantation are very different from the circumstances under which patients with chronic liver disease are transplanted, and therefore waiting list management for acute and urgent patients is discussed separately in Section 6.3.3.

Organisation of liver transplantation in Australia and New Zealand

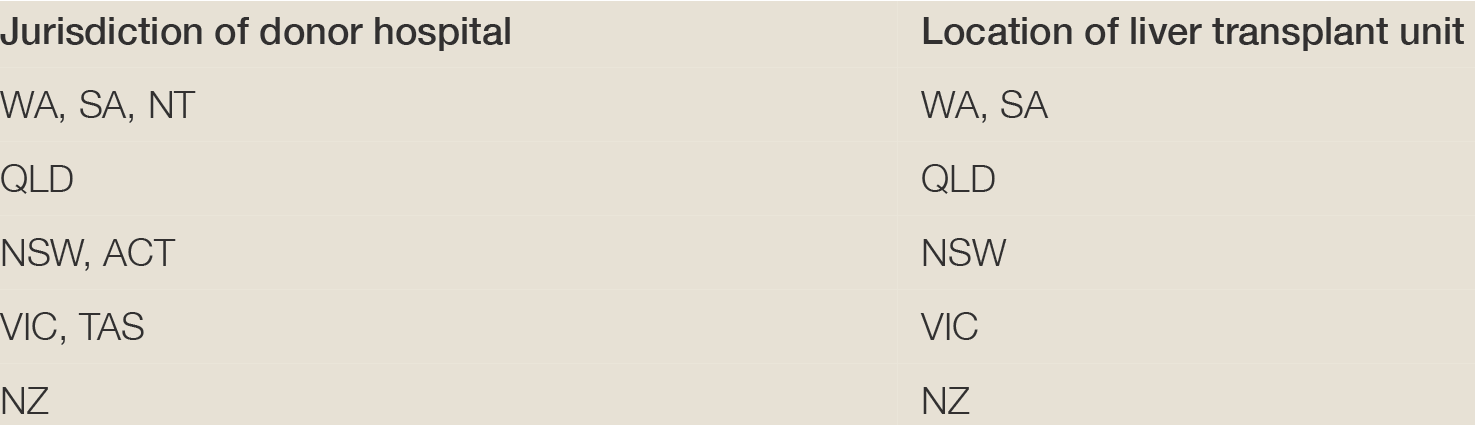

Each state in Australia has a single liver transplant unit. There is a single unit in Auckland that serves New Zealand. The New Zealand unit is broadly aligned with the units in Australia and participates in the sharing of donor livers between the jurisdictions as described in Section 6.5. The liver transplant units and their corresponding donor jurisdictions are as follows:

Each of the liver transplant units also undertakes multi-organ donor retrieval procedures as a service for the organ donation agencies that exist in each jurisdiction. Although the population of Australia and New Zealand is small compared to many European countries, the geography is very different – each liver transplant unit in Australia covers an area bigger than Western Europe and this is one of the reasons why organ allocation is organised on a jurisdictional, rather than national, basis.

6.2 Recipient eligibility criteria

6.2.1 Inclusion criteria

As a general principle, eligibility is restricted to patients for whom quality and quantity of life is expected to be enhanced by liver transplantation. Given the limited availability of donor organs and the risks to the patient of liver transplant surgery, patients will only be listed for liver transplantation once their liver disease poses an imminent threat to their survival or their quality of life has become intolerably poor.

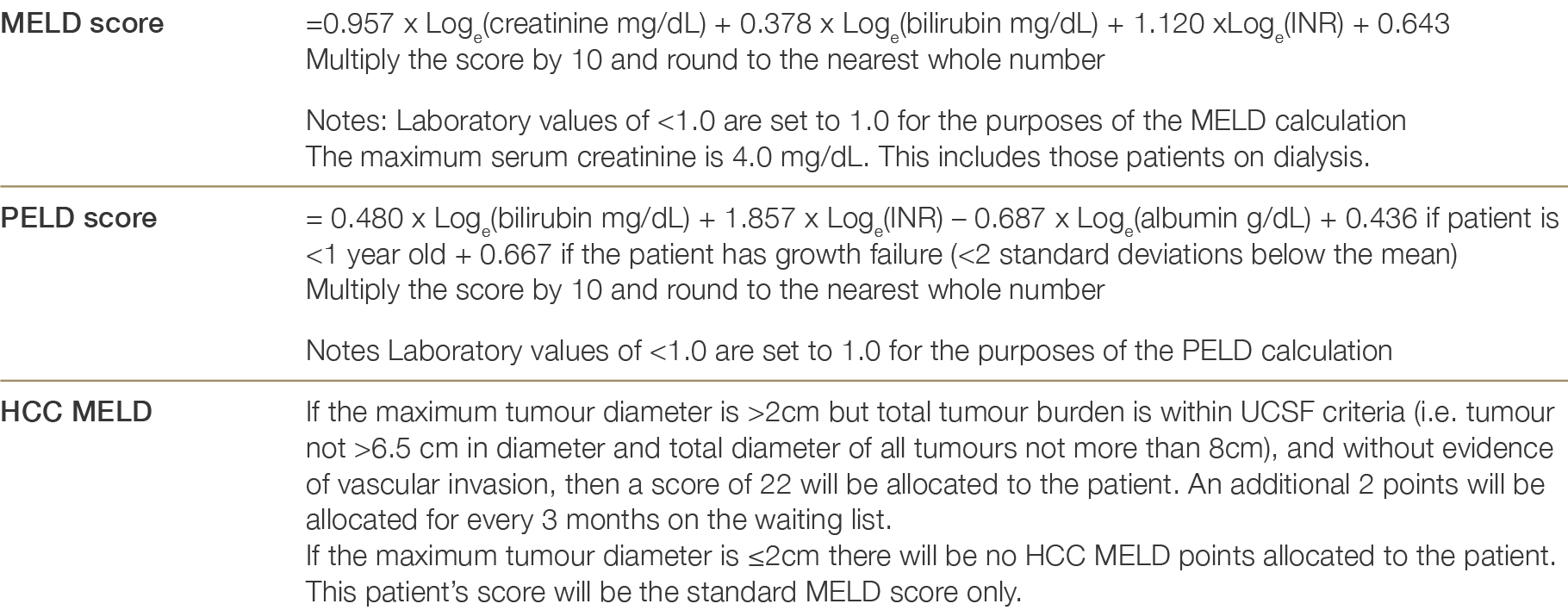

Liver disease has many different manifestations and, in contrast to renal disease, it is difficult to describe the severity of an individual’s liver disease with a single metric. In the United States in the late 1990s it was recognised that access to and timing of liver transplantation varied greatly around the country—some patients whose health was barely impacted by their liver disease were receiving transplants whilst many others died before receiving a lifesaving transplant. This stimulated the development of a scoring system, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, which correlates with how long a patient is likely to survive without a liver transplant (Table 6.1: Calculation of MELD, PELD and HCC MELD scores).

MELD score is a measure of the severity of an individual’s liver failure, calculated using a mathematical formula based on blood tests: the higher the score, the greater the severity of liver failure. The Paediatric End-Stage Liver Disease (PELD) score is an equivalent system adjusted for children. The score has a reasonable, but not perfect, ability to predict the risk of dying from liver failure in the near future (3 months). It has allowed jurisdictions in the United States to allocate livers based on need alone. This is particularly important where many centres ‘compete’ for donor livers, and the MELD score-based allocation system has been implemented to reduce ‘gaming’ of the system by individual centres for their own, and their patient’s benefit. It must be recognised, however, that it is quite common to have severe liver disease, posing an imminent threat to life, where the MELD score is still relatively low. In Australia and New Zealand, where all livers go to a single centre (i.e. there is no competition) the liver can be allocated to the individual with the truly greatest need even if they do not have the highest MELD score. In Australia and New Zealand, the patients are ranked within each transplant centre according to clinical need, which takes into account their MELD scores but also other less easily measured factors.

There are some patients who, although their survival is not immediately threatened, have an intolerably poor quality of life as a result of their liver disease. The best example would be patients with polycystic liver and kidney disease, for whom liver function may not be impaired but the liver can reach such a size that it completely fills their abdominal cavity and results in starvation because the patient becomes physically unable to eat.

Typical indications for liver transplantation in patients with chronic liver disease are:

MELD score of >15 in an adult or a PELD score of >17 in a child (see Table 6.1: Calculation of MELD, PELD and HCC MELD scores)33 Lake JR. MELD – an imperfect but thus far the best solution to the problem of organ allocation. J Gastrointestinal & Liver Dis, 2008;17(1):5–7. ×

HCC that fulfils accepted transplant eligibility criteria (see 6.2.3) criteria44 Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of the proposed UCSF criteria with the Milan criteria and the Pittsburgh modified TNM criteria. Liver Transplantation, 2002;8(9):765–74. ×

Liver disease that would result in a two-year mortality risk of >50% without liver transplantation

Diuretic-resistant ascites

Recurrent hepatic encephalopathy

Recurrent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Recurrent or persistent gastrointestinal haemorrhage

Intractable cholangitis (in primary or secondary sclerosing cholangitis patients)

Hepatopulmonary syndrome55 Krowka MJ, Mandell MS, Ramsay MAE, et al. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: A report of the multicenter liver transplant database. Liver Transplantation, 2004; 10(2):174–82. ×

Portopulmonary hypertension55 Krowka MJ, Mandell MS, Ramsay MAE, et al. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: A report of the multicenter liver transplant database. Liver Transplantation, 2004; 10(2):174–82. ×

Metabolic syndromes (with severe or life-threatening symptoms) that are curable with liver transplantation (e.g. familial amyloidosis, urea cycle disorders, oxalosis etc.)

Polycystic liver disease with severe or life-threatening symptoms

Intractable itch secondary to cholestatic liver disease

Hepatoblastoma in children

Severe alcoholic hepatitis not responding to medical therapy in appropriately selected patients (see Section 6.2.4).

Table 6.1: Calculation of MELD, PELD and HCC MELD scoresaa No reference text available.×

a http://www.unos.org/resources/meldpeldcalculator.aspa No reference text available.×

6.2.2 Exclusion criteria

Patients who are estimated to have less than a 50% likelihood of surviving at least five years after liver transplantation, and patients who are predicted to have an unacceptably poor quality of life post-transplant, are considered ineligible for wait-listing. Exclusion criteria therefore include those conditions or circumstances (medical or psychosocial) that would make the risk of mortality at five years post-transplant exceed 50%. The assessment of risk associated with coexisting conditions is complex and many patients require detailed appraisal by specialists across multiple fields before determining whether a patient should be excluded from entry to the waiting list. The NHMRC Ethical Guidelines underpin the specified exclusion criteria.2 Past behaviours such as intravenous drug use or alcohol dependence are not acceptable as reasons for exclusion from the liver transplant waiting list, but if these behaviours are ongoing then they would be considered exclusionary as they threaten the outcome of the transplant. The following list of contraindications to liver transplantation is indicative but not exhaustive:2 National Health and Medical Research Council (2025). Ethical guidelines for cell, tissue and organ donation and transplantation in Australia. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council. ×

Malignancy: prior or current, except for HCC within criteria outlined in 6.2.3.1 and small intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma 6.2.3.2).6 These cases often require detailed discussion between transplant units and oncologists prior to the patient being assessed for transplantation because the prognosis of different cancers varies widely6 Kauffman HM, Cherikh WS, McBride MA, et al. Transplant recipients with a history of a malignancy: risk of recurrent and de novo cancers. Transplantation Reviews, 2005;19(1):55–64. ×

Active infection (other than hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or HIV)—tuberculosis would be an example

Coronary artery disease that is irremediable or associated with a poor prognosis

Cerebrovascular disease that is irremediable or associated with a poor prognosis

Severe metabolic syndrome (hypertension, morbid obesity, hyperlipidaemia, and type II diabetes, with or without obstructive sleep apnoea)77 Dick AA, Spitzer AL, Seifert CF, et al. Liver transplantation at the extremes of the body mass index. Liver Transplantation, 2009; 15(8):968–77. ×

Extreme inanition or frailty not thought to be reversible by liver transplantation

Patients at significant risk of a return to hazardous alcohol intake: for those patients where alcohol was a contributing factor in their liver disease, careful assessment by a multidisciplinary team of the risk to post-transplant outcomes posed by recidivism is required. As a general rule, a period of abstinence of not less than six months will need to be observed before acceptance onto the waiting list to exclude patients with alcohol related liver disease whose liver function will improve with abstinence to the point where liver transplantation is no longer needed.8 If assessment of a return to hazardous drinking risk is unfavourable then this is a contra-indication to proceeding with transplantation because of the risk of compromised outcomes. Patients considered for transplantation for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis (AH) do not require a specified period abstinence but must fulfil additional inclusion and exclusion criteria (6.2.4).8 McCallum S and Masterton G. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: Asystematic review of psychosocial selection criteria. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 2006;41(4):358–63. ×

Ongoing misuse of any substance that might compromise survival of the graft

A likelihood that the recipient will be unable to adhere to the necessary ongoing treatment regimen and health advice after transplantation

Tobacco use is a relative contraindication to liver transplantation (because of an increased risk of malignancy and cardiovascular disease)9,109 van der Heide F, Dijkstra G, Porte RJ, et al. Smoking behaviour in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transplantation, 2009; 15(6):648–55. 10 Borg MAJP, van der Wouden E, Sluiter WJ, et al. Vascular events after liver transplantation: a long term follow-up study. Transplant International, 2008; 21(1):74–80. ×

Inadequate or absent social support is a relative contraindication to liver transplantation (because of an increased risk of non-adherence)11,1211 Dobbels F, Vanhaecke J, Desmyttere A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported pretransplant non-adherence with medication in heart, liver and lung transplant candidates. Transplantation, 2005; 79(11):1588–95. 12 Teeles-Cooeia D, Barbosa A, Mega I, et al. Adherence correlates in liver transplant candidates. Transplantation Proceedings, 2009;41(5):1731–34. ×

Hepatopulmonary Syndrome: current evidence shows that patients with this condition who have a partial pressure of oxygen on room air of <40 mmHg have an unacceptably high perioperative mortality rate (30 to 40%)55 Krowka MJ, Mandell MS, Ramsay MAE, et al. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: A report of the multicenter liver transplant database. Liver Transplantation, 2004; 10(2):174–82. ×

Portopulmonary hypertension: current evidence shows that patients with this condition who have, despite treatment, a mean pulmonary artery pressure of >35 mmHg and a pulmonary vascular resistance of >250 dynes.sec.cm-5 (3.1 Woods units)7 have an unacceptably high perioperative mortality rate (30 to 40%, with patients often succumbing during the transplant surgery)55 Krowka MJ, Mandell MS, Ramsay MAE, et al. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: A report of the multicenter liver transplant database. Liver Transplantation, 2004; 10(2):174–82. ×7 Dick AA, Spitzer AL, Seifert CF, et al. Liver transplantation at the extremes of the body mass index. Liver Transplantation, 2009; 15(8):968–77. ×5 Krowka MJ, Mandell MS, Ramsay MAE, et al. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: A report of the multicenter liver transplant database. Liver Transplantation, 2004; 10(2):174–82. ×

Neurocognitive impairment is not an absolute exclusion criterion, but all units are aware that such patients and their carers may find that the outcome of transplantation is not as good as they hoped, with little improvement in quality of life. Patients with severe neurocognitive impairment require an exceptionally careful evaluation.

6.2.3 Malignancy assessment

6.2.3.1 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

In Australia and New Zealand, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 25% of liver transplants either as a primary or a secondary indication and currently carries a 5-year post-transplant survival of approximately 84%13 . HCC typically arises in a setting of chronic liver disease and is an unusual malignancy in an otherwise normal liver. Any patient with cirrhosis has an increased risk of HCC, but that risk is greater in liver disease arising from certain causes such as hepatitis B and hepatitis C. While patients with a single small HCC can sometimes be treated with liver resection or ablation, others can only be cured by liver transplantation. Establishing which HCC patients are eligible for transplantation is complex. There is substantial heterogeneity in the way that tumours behave, and predicting the natural history of disease progression in the HCC patient is not straight forward. Furthermore, the “severity” or stage of a HCC is variable, and it has been established for more than two decades that there is a high risk of recurrence and death if liver transplantation is performed in the context of advanced HCC.13 Australia and New Zealand Liver and Intestinal Transplant Registry Annual Report 2019 Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Editors: Michael Fink, Mandy Byrne. ×

Several transplant eligibility criteria have been developed for HCC by correlating pre transplant HCC characteristics with survival outcomes. The Milan criteria established that limiting tumour burden to a solitary lesion less than 5cm or up to 3 lesions each no more than 3cm in diameter and in the absence of vascular invasion or extrahepatic disease, improved post-transplant recurrence-free survival.14 Expansion of the original Milan criteria, as proposed by the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) group,15 or the extended Milan “up-to-7 rule”16 amongst others, has demonstrated that less restrictive criteria can be used without impacting survival.14 Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693-9. ×15 Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology 2001;33:1394-403. ×16 Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:35-43. ×

UCSF eligibility criteria

In Australia and New Zealand, the UCSF criteria of up to 3 lesions measuring no larger than 4.5cm in diameter and adding to a total tumour diameter of 8cm or less, or a single tumour up to 6.5cm, have been adopted for liver transplant waitlisting. The prognostic value of alpha fetoprotein (AFP) as a surrogate of microvascular invasion and as a predictor of poor post-transplant outcomes in HCC has also been established.17-19 An AFP cut-off of >1000 ng/mL has been recommended in Australia and New Zealand as an exclusion for liver transplantation in line with current US guidelines,20 however more restrictive cut-offs have been used in other countries.21 By adding AFP cut-offs to waitlisting and/or downstaging models, improvements in predicting post-transplant outcomes have been demonstrated.18, 22-2417 Berry K, Ioannou GN. Serum alpha-fetoprotein level independently predicts posttransplant survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2013;19:634-45. 18 Duvoux C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Decaens T, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model including alpha-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria. Gastroenterology 2012;143:986-94 e3; quiz e14-5 19 Hameed B, Mehta N, Sapisochin G, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein level > 1000 ng/mL as an exclusion criterion for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma meeting the Milan criteria. Liver Transpl 2014;20:945-51. ×20 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. OPTN/ UNOS Liver and Intestinal Organ Transplantation Committee. [https:// optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1922/liver_hcc_criteria_for_auto_approval_20160815.pdf] Accessed July 1, 2019 ×21 Canadian Society of Transplantation Liver Listing and Allocation Forum Report and Recommendations 2016. [https:// professionaleducation.blood.ca/sites/msi/files/liver_listing_and_allocation_forum_report_-_final_en.pdf]. Accessed July 2, 2019/. ×18 Duvoux C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Decaens T, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model including alpha-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria. Gastroenterology 2012;143:986-94 e3; quiz e14-5 22 Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014 Dec;61(6):1385-96. 23 Toso C, Meeberg G, Hernandez-Alejandro R, et al. Total tumor volume and alpha-fetoprotein for selection of transplant candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective validation. Hepatology 2015;62:158-65. 24 Mazzaferro V, Sposito C, Zhou J, et al. Metroticket 2.0 Model for Analysis of Competing Risks of Death After Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2017. ×

Metroticket 2.0 eligibility criteria

The Metroticket 2.0 model uses pre-transplant imaging and AFP to predict post-transplant HCC-recurrence free and overall survival24. This model has several potential advantages over existing criteria based on tumour size alone. Firstly, the model was derived and validated using pre-transplant radiology tumour characteristics rather than explant histology, pragmatically representing the point of decision making in clinical practice. Secondly, a competing risks analysis was performed, which identified non-HCC related death as a competing risk with HCC-related death and provided more accurate survival estimates. Thirdly, the Metroticket 2.0 model can be used as an individual risk calculator for five-year HCC-specific and overall survival or as a dichotomous (in/out) criteria. Validation of the Metroticket 2.0 model using data from all the Australian and New Zealand liver transplant units found that patients fulfilling the Metroticket 2.0 criteria on explant have a survival comparable to those using UCSF criteria, which was similar to single-centre Australian data using pre-transplant imaging. Thus, expansion of criteria to MT2 is justifiable.2524 Mazzaferro V, Sposito C, Zhou J, et al. Metroticket 2.0 Model for Analysis of Competing Risks of Death After Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2017. ×25 Barreto, S.G.; Strasser, S.I.; McCaughan, G.W.; Fink, M.A.; Jones, R.; McCall, J.; Munn, S.; Macdonald, G.A.; Hodgkinson, P.; Jeffrey, G.P.; Jaques, B.; Crawford, M.; Brooke-Smith, M.E.; Chen, J.W. Expansion of Liver Transplantation Criteria for Hepatocellular Carcinoma from Milan to UCSF in Australia and New Zealand and Justification for Metroticket 2.0. Cancers 2022, 14, 2777. ×

There are several important caveats to using the Metroticket 2.0 model. The vast majority of patients in the derivation cohort of the Metrocket 2.0 model received TACE or other neoadjuvant treatments. The measurements that were used to derive the model were based on the most recent imaging and AFP prior to transplant, not the measurements at listing. Nodules were only counted if they remained arterialized after neoadjuvant treatment and nodule size was taken to include the largest diameter of both viable and non-viable portions. It follows that in applying the prognostic model, tumour number and size need to be defined and measured in the same way.

Downstaging

Factors such as lack of tumour response to transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or atypically aggressive tumour biology have been correlated with poor post-transplant outcomes26. A period of close observation may be required to confirm that tumour burden remains firmly within transplant eligibility criteria. In the setting where potential transplant candidates have tumour burden in excess of UCSF or Metroticket 2.0, loco-regional therapy such as TACE may be offered to reduce the tumour burden to downstage to within transplant criteria. If downstaging is offered, then potential transplant recipients must demonstrate that they remain within transplant eligibility criteria for a minimum observation period of 3 months before being considered for waitlisting27. As aforementioned, the Metroticket 2.0 prognostic model was derived using measurements that include the influence of downstaging, although the model has not been specifically validated in this setting. Patients may be downstaged to within Metroticket 2.0, UCSF or Milan criteria, depending on individual transplant unit preference, however such patients should be reassessed after a minimum 3-month observation period before being activated on the waiting list.26 Otto G, Schuchmann M, Hoppe-Lotichius M, et al. How to decide about liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: size and number of lesions or response to TACE? J Hepatol 2013;59:279-84. ×27 Clavien PA, Lesurtel M, Bossuyt PM, et al. Recommendations for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an international consensus conference report. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e11-22. ×

Allocation priority

Another complex issue is determining the priority of HCC patients on the liver transplant waiting list. The is no confirmed optimal method of prioritising HCC patients to ensure they are transplanted before they are ineligible due to tumour progression, while also ensuring non-HCC patients are not disadvantaged. Assigning additional MELD points to HCC patients on the waiting list and other systems have been suggested, but with varying degrees of success28. In Australia and New Zealand, waiting list prioritisation remains the responsibility of the individual transplant unit. The burden of HCC continues to rise and ensuring equitable organ allocation remains a pertinent issue for the future.28 Heimbach JK, Hirose R, Stock PG, et al. Delayed hepatocellular carcinoma model for end-stage liver disease exception score improves disparity in access to liver transplant in the United States. Hepatology 2015;61:1643-50. ×

Recommendation

UCSF criteria or Metroticket 2.0 are the eligibility criteria for liver transplant waitlisting in Australia and New Zealand.

AFP >1000 ng/mL should be considered as an exclusion for liver transplant waitlisting.

The Metroticket 2.0 model is acceptable for liver transplant waitlisting. The listing threshold may be set by individual units but must be predictive of at least 70% HCC-specific 5-year survival.

Metroticket 2.0, UCSF or Milan may be used as downstaging criteria. Any patient who is offered downstaging must remain within the respective criteria for a minimum 3-month observation period prior to activation on the waiting list.

6.2.3.2 Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Small intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is now accepted as a primary indication for liver transplantation.

Although actual or suspected cholangiocarcinoma has historically been a major contraindication to liver transplantation, recent international publications have demonstrated good outcomes for a subset of patients with the following strict criteria:

solitary (although there could be co-existing HCC within HCC criteria (6.2.3.1))

small ≤ 20mm

intra-hepatic

unresectable, and in the presence of cirrhosis of the liver

have no evidence of metastasis (including local lymph nodes).

The lesion can be the primary indication for transplantation if the diagnosis is relatively certain or there is another co-existing indication such as chronic liver disease. Biopsy of suspicious lesions is discouraged due to the small risk of tumour seeding. PET scanning is not required prior to transplantation.

Reasonable efforts to rule out other diagnoses such as metastasis from the GI tract should be undertaken (such as CT imaging, tumour markers, and appropriate endoscopic examinations). There is no requirement for neo-adjuvant therapy prior to transplantation.

Screening for new or metastatic lesions and lesion growth beyond 20mm while awaiting transplant should occur at least every 3 months by CT or MRI imaging. Delisting will occur if the tumour breaches the criteria above.

The role of post-transplant adjuvant chemotherapy or immunosuppressive modulation will be based on the post-transplant histology and be at the discretion of the local transplant team and oncology recommendations.

6.2.4 Early transplantation for severe acute alcoholic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a clinical entity that is usually, but not always, diagnosed by biopsy. Severe AH that fails to respond to medical therapy has a mortality of 70% at two months.29 Liver transplantation is the only lifesaving treatment for these patients. International data suggests that the three-year survival of carefully selected patients transplanted for a first episode of alcoholic hepatitis is equivalent to that of patients transplanted for other indications.30-32 The survival and comparatively low alcohol relapse rates suggest the feasibility of performing liver transplantation in this group of patients in Australia in those units that have the necessary resources for patient assessment and post-transplant alcohol related follow up. In those units that have an active AH policy the following are required.29 Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic Hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2758-2759 2011;365(19):1790-1800. ×30 Mathurin P, Moreno C, Samuel D, et al. Early liver transplantation for Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2011;365(19):1790-1800. 31 Lee BP, Mehta N, Platt L et al. Outcomes of Early Liver Transplantation for Patients with Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis. Gastroenterology, 2018 Aug;155(2):422-430. 32 Im GY, Kim-Schluger L, Shenoy A et al, Early Liver Transplantation for Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis in the United States – A Single Centre Experience. Am J Transplant 2016;16:841-846. ×

Inclusion criteria:

Patients must meet the specific definition of severe AH:33

a. Onset of jaundice within prior 8 weeks

b. Ongoing consumption of at least >40g for women and >60g for men of alcohol/day for six months or more, with less than 60 days of abstinence before onset of jaundice

c. AST and ALT > 50 IU/L but <400 IU/L

d. Bilirubin > 50mmol/L

e. Liver biopsy confirmation (strongly recommended)

f. Maddrey Score of >32 AND MELD score >2033 Crabb D, Bataller R, Chalasani R et al. NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia: Standard Definitions and Common Data Elements for Clinical Trials in Patients with Alcoholic Hepatitis: Recommendation from the NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia. Gastroenterology 2016;150:785-790. ×Patient must be a non-responder to appropriate medical therapy—for most patients this will be corticosteroids managed as per Lille criteria, though some patients will have a contraindication to steroids

Presentation of severe AH must be the first liver decompensating event

Favorable psychosocial profile as determined by multidisciplinary team

Consensus agreement by the unit’s transplant committee.

Exclusion criteria (in addition to those listed in Section 6.2.2)

Prior documented diagnosis of advanced alcohol related liver disease such as cirrhosis or previous decompensating liver event (e.g. jaundice, ascites, variceal bleed)

Presence of severe alcohol use disorder as classified by DSM V (previously termed alcohol dependence)

Absence of insight into alcohol as cause of liver disease / current presentation

Absence of agreement by patient to adhere to lifelong total alcohol abstinence and participate in long term post-transplant relapse and monitoring.

At the outset, patients should be diagnosed with dual pathology of both alcohol use disorder and liver disease. For optimal outcomes, both conditions should be managed in the long term with equal attention. Alcohol relapse prevention should be integrated into post transplant management in a structured way, preferably with regular alcohol biomarker monitoring. Relapse prevention should be multidisciplinary and evidence based, performed by an experienced practitioner skilled in a variety of psychotherapeutic techniques. Consideration should be given to pharmacotherapy for patients with ongoing cravings. There should be rapid identification and simple pathways to escalate support for those patients identified as having “slipped” to prevent the return to the pattern of sustained drinking.

6.2.5 Retransplantation

Patients are eligible for re-transplantation if they fulfil the same criteria for either acute or chronic liver disease as stated above, with an estimated likelihood of surviving at least five years post-retransplantation exceeding 50%.

6.3 Waiting list management

6.3.1 Principles of prioritisation for liver transplantation

For patients with chronic liver disease who are waitlisted for liver transplantation, care is provided at one of the Australian or New Zealand liver transplant units, which co-align with organ donation services. It is logistically complex to transport donor livers around Australia and New Zealand; furthermore, organ donation rates are such that it is most efficient to organise liver transplant services at the state level. Therefore livers donated in a given jurisdiction are allocated to patients on the waiting lists of the transplant units that correspond to that donor jurisdiction (unless there is a patient on the urgent waiting list—see Section). It is therefore necessary for each liver transplant unit to be very familiar with the patients on their waiting list and to prioritise them according to clinical urgency in order to minimise waiting list mortality.

Patients on the liver transplant waiting list are grouped according to the blood group of the donor liver that the patient on the waiting list would ideally receive, and then prioritised according to clinical urgency within each blood group. The waiting list is organised in this way to promote equitable outcomes across recipient blood groups. Usually this will mean that recipients will receive only a liver with the identical blood group to their own. However, in some circumstances where a patient is extremely unwell, they might receive a liver that would otherwise have been allocated to other blood group lists. For example, a blood group O liver can be transplanted into a patient of any blood group, and this may occasionally be necessary to save the life of a very sick patient of another blood group. Conversely, subtype 2 of blood group A is compatible with blood group O, and hence A2 livers can be transplanted into O recipients. Blood group incompatible transplants can also be performed, but these are rare and only performed when patient risk assessment suggests that it is justified and certain technical manipulations are undertaken.

Prioritisation is NOT based on the length of time that patients have been on the liver transplant waiting list: the principle guiding liver allocation is always “sickest first”. Prioritisation is based largely on MELD score, but other features of liver disease (such as encephalopathy) may justify prioritisation above patients with higher MELD scores. In the United States, such patients are termed “MELD exceptions” in recognition that their MELD scores don’t serve them equitably, and there is a complex protocol in place to enhance their priority. An example would be patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis, who are prone to serious recurrent bacterial cholangitis with blood poisoning yet who frequently have low MELD scores. There are also a number of rare diseases where the liver doesn’t fail but has a metabolic defect—in the manufacture of an important protein for example—which leads to life threatening disease in another organ system (amyloidosis is an example). The liver transplant units in Australia and New Zealand work out how to prioritise such patients on their own individual waiting lists.

Each unit reviews their waiting list at least weekly and discusses the priority of listed patients. In this way, patients who deteriorate—especially if this isn’t reflected in their MELD score—can be re-prioritised. In Australia and New Zealand, prioritisation occurs by clinical consensus among all members of the transplant unit. At the time of a liver donor offer the selection of a recipient is then relatively straightforward and can be made by one or two individuals rather than the entire clinical group, as patients have been ranked by need ahead of time.

6.3.2 Ongoing review

In the same way that a patient listed for urgent liver transplantation can deteriorate to a point where transplantation becomes futile, so might non-urgent patients need to be delisted because their situation has changed in such a way that they are no longer likely to benefit a from liver transplant. The commonest reason for this is cancer progression in patients with HCC, where the tumour(s) has grown to the point where the risk of recurrence after transplant is unacceptably high.

Clinical circumstances can arise that mean that a patient needs to be temporarily removed from the ‘active’ waiting list. An example would be a significant infection, causing an acute illness such that liver transplantation at that time would be hazardous. These patients are placed on a ‘hold’ list that allows them to still be reviewed at the transplant unit clinical meetings and, when appropriate (e.g. after the infection is successfully treated), they can be returned to the active list or permanently delisted if necessary. Patients are informed of such changes in listing status whenever they occur. The reasons for the status change should be made clear to the patient or, if appropriate, to their next of kin.

6.3.3 Acute and urgent patients

There are situations in which the need for liver transplantation occurs suddenly and without a history of pre-existing liver disease. This can happen in patients newly infected with hepatitis B where the liver is rapidly overwhelmed by the virus. Paracetamol poisoning is another example. However, in some patients no cause of acute liver failure can be established. There is also a small risk in patients who have recently undergone liver transplantation that the donor liver may not work, due either to primary non-function or hepatic arterial thrombosis. Many patients with acute liver dysfunction will recover spontaneously as the liver cells overcome the causative insult—only a few patients will actually require urgent liver transplantation.

In Australia and New Zealand, the King’s College criteria, first devised in 1989, are used to guide whether a patient might need urgent liver transplantation. It is recognised that there are limitations to the use of the King’s College Criteria in the era of early renal replacement therapy for neuroprotection, and markedly improved transplant-free outcomes than were originally reported related to critical-care improvements. It is recognised that the urgency of the situation is not always the same from one patient to another—in the most extreme cases, where the patient is in a coma and on a ventilator (life support), the patient may have less than 24 hours to live and is placed in Category 1. Less serious cases, where the data indicate severely impaired liver function, but the patient is not yet ventilated, are placed in Category 2a. See Table 6.2 for all urgent liver listing categories.

King’s College Hospital criteria for liver transplantation in acute liver failure Paracetamol (acetaminophen)-induced liver failure:

pH of arterial blood (after rehydration) of <7.3, OR all three of the following criteria on the same day:

International normalised ratio (INR) >6.5

Serum creatinine >300 micromol/L

Grade III or IV encephalopathy.

Non-paracetamol-induced acute liver failure:

INR >6.5, OR three of the following five criteria:

Age <11 or >40

Serum bilirubin >300 micromol/L

INR >3.5

jaundice-to-encephalopathy time of >7 days

Drug-induced liver injury or viral hepatitis as aetiology.

For urgent liver transplantation, recipient prioritisation and allocation of donor livers is conducted on an Australia and New Zealand-wide basis (i.e. binational listing). This is because the populations served by the individual jurisdictions (Australian States and New Zealand) are too small to realistically offer a good chance of a donor liver becoming available for urgent patients in the necessary timeframe. It has been agreed that patients fitting the criteria for urgent listing should have access to donor livers across all of Australia and New Zealand. Since less than 10% of liver transplants are performed in urgent patients, this does not seriously impact upon waitlisted patients with chronic liver disease. However, to reduce the possibility that patients with chronic liver disease might be adversely affected by urgent listings, two categories of urgency exist.

Extremely sick patients are placed in Category 1: any donor liver that becomes available anywhere in Australia or New Zealand is automatically offered to a patient in Category 1. It is possible, however, that there might be patients with chronic liver disease who are on the waiting list and, although not listed as urgent, may be at greater risk of dying than an urgent patient in Category 2a. Thus, when a donor liver becomes available in a given jurisdiction and there is a Category 2a patient listed elsewhere in Australia or New Zealand, a discussion needs to occur between the transplant unit in the jurisdiction listing the Category 2a patient, and the transplant team in the donor home state to ensure that the liver is in fact directed to the sickest patient. In practice, this is usually to the Category 2a patient.

There are two further types of Category 2 patients. Category 2b, which refers to children with hepatoblastoma in whom liver transplantation needs to occur quickly at the conclusion of chemotherapy treatment so that cure can confidently be achieved; and Category 2c, which refers to patients who need combined liver and intestinal (small bowel) transplantation.

It is exceptionally difficult to find suitable grafts for Category 2c patients, who also present a formidable surgical challenge as well as having a high risk of dying whilst they await transplantation. It has been agreed across allliver transplant units that Category 2c patients will be assigned national prioritisation, however, it has also beenagreed that donor livers will not be sent to the National Intestinal Transplant Unit (part of the Liver Transplant UnitVictoria) if the jurisdiction in which the liver was donated has a patient on their waiting list with a MELD score of25 or greater (such patients have a 50% chance of death within a month).

In the case of both Category 2b and Category 2c patients, discussion regarding liver allocation needs to take place between the urgent listing unit and donor home state transplant unit before allocation takes place.

Patients with high MELD scores in Australia and New Zealand historically had limited access to deceased donor livers. To address this, binational sharing of donor livers for patients with a MELD score ≥35 was introduced in February 2016, now known as Share 35. The Share 35 process is a liver transplant allocation policy aimed at reducing waiting list mortality and maximising the utility of donated livers. It prioritises patients with a MELD score of 35 or higher, offering waitlisted patients with MELD ≥35 an opportunity to be considered for a transplant, beyond that of home state offers. Since the implementation of the Share 35 policy, there has been a 78% reduction in waiting list mortality, with post-transplant survival remaining equivalent and overall intention-to-treat survival improving.34 A discussion regarding liver allocation between the Share 35 listing unit and the donor home state transplant unit is encouraged, though not compulsory, prior to allocation.34 Fink MA, Gow PJ, McCaughan GW, et al. Impact of Share 35 liver transplantation allocation in Australia and New Zealand. Clin Transplant. 2024; 38:e15203. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.15203 ×

Table 6.2: Categories of patients eligible for urgent liver transplantation

Category 1

Patients suitable for transplantation with acute liver failure who are ventilated and in an ICU at risk of imminent death. When such patients are listed, allocation to them is mandatory.

Category 2

When a donor liver becomes available, discussion occurs between the urgent listing unit and the donor home state transplanting unit to determine optimal allocation

Category 2a

Patients suitable for transplantation with acute liver failure from whatever cause who are not yet ventilated but who meet the King’s College criteria. This includes patients who have acute liver failure because of vascular thrombosis in a liver allograft. In addition, this category includes paediatric candidates with severe acute or chronic liver disease who have deteriorated and are in a paediatric intensive care unit. When such patients are listed, allocation to them is usual but not mandatory. It is subject to discussion between the directors (or delegates) of donor and recipient state liver transplant centres across Australia and New Zealand.

Category 2b

Paediatric patients suitable for transplantation who suffer from severe metabolic disorders or hepatoblastoma (after initial treatment) for whom a limited time period exists during which liver transplant is possible.

Category 2c Patients awaiting combined liver-intestinal transplantation by the National Intestinal Transplantation programme in Victoria. If a potentially suitable donor is identified, the donor home state transplant unit must discuss allocation of donor organs with the Victoria unit unless the donor home state transplant unit has a suitable liver recipient with a MELD score of 25 or greater.

Share 35

Patients with chronic liver disease awaiting liver transplant who have, or progress to, a MELD score of 35 or higher can be listed under the Share 35 programme. Share 35 patients are listed across all liver transplant units in Australia and New Zealand; however, they are categorised separately from urgent listings.

It is not compulsory to offer to Share 35 patients, a decision is made by the donor home state transplant unit whether to offer on or not. A discussion between units is encouraged but not compulsory.

Listing and delisting of acute and urgent patients

Patients meeting criteria for Urgent or Share 35 listing are registered on OrganMatch by the home-unit. The assessment of patients needing urgent liver transplantation is complex, and the situation is never static. Some acute patients improve while they are waiting for a donor organ, and therefore can be removed from the waiting list (delisted) because they no longer need a transplant to survive. Other patients unfortunately deteriorate while waiting for an urgent liver transplant and may reach a point where transplantation is futile, in which case they must be delisted. An example of this would be the onset of brain swelling when, even if a transplant is undertaken, the ensuing brain damage cannot be reversed and would prove fatal.

Patients listed for urgent liver transplantation must be frequently re-assessed. The listing automatically expires after 72 hours for Category 1 and Category 2a patients, and after 7 days for category 2b and Share 35 patients, so that patients must be formally relisted in OrganMatch at these time points if liver transplantation is still required. Category 2c are exempted from the relisting requirements because they are not in a situation where their condition is expected to improve (however, they may require delisting if there is a change in circumstances such that transplantation is no longer appropriate). Please also refer to the OTA/TSANZ National Standard Operating Procedure: Organ Allocation, Organ Rotation, Urgent Listing for urgent listing procedures.

6.4 Donor assessment

All donor organs are precious, and the altruistic act by donor families of consenting to deceased donation in the most difficult and tragic of circumstances is gratefully and respectfully acknowledged. The goal of organ transplantation is to save and improve lives; in some circumstances, however, a potential donor liver may carry some risk of not achieving this goal. The worst case scenario is that the liver does not function after transplantation, in which case the recipient of that liver will die (unless a second donor liver quickly becomes available). There is also the potential transmission of infection or cancer from the organ donor to the recipient via the donor liver (see Chapter 2).

The assessment of donor eligibility and the suitability of organs for transplantation is one of the most difficult and complex areas of liver transplantation. Decision-making is frequently not straightforward: patients on the waiting list are at risk of dying without a transplant so it may be preferable to accept a higher-risk donor liver when offered rather than wait for a lower-risk one, not knowing how long that wait might be. Of course, the risk-benefit calculation is not the same for all patients. The HCC patient with a tumour that is approaching the size threshold for delisting will present a different risk-benefit scenario with regards to utilisation of a higher-risk donor liver as compared to stable a patient with cirrhosis from hepatitis C. Balancing the risks associated with a given donor organ against recipient urgency is one of the most difficult tasks faced by liver transplant units.

During the assessment and workup of potential liver transplant recipients, donor-related risk as it relates to the individual patient needs to be thoroughly explained as part of the consent process. Thus, a patient who is very unwell and at high risk of imminent death may be advised to accept a higher-risk liver—for example, a liver retrieved from a donor carrying the hepatitis B virus. The recipient of this graft may then require lifelong anti-viral treatment, but this may be acceptable if such a donor liver represents the only opportunity for this very sick patient to receive a transplant. On the other hand, a liver from a hepatitis B-positive donor or other higher-risk donor might not be suitable for a young child.

As well as the general donor eligibility criteria described in Chapter 2, there are some specific donor considerations relevant to liver transplantation. In contrast to the considerations related to higher-risk donor organs, it is also possible to identify donor livers that carry very low risk of either immediate or long-term dysfunction. In the case of low-risk livers, there is a commitment in Australia and New Zealand that these will be “split” wherever possible—typically generating a small left-sided graft and a larger right-sided one. Thus the single donor liver can be transplanted into two people. This is especially relevant to the transplantation of children, who usually only require a small graft—the left side being ideal. Such donors are young (less than 50 years of age), have been diagnosed with neurological death, have no risks factors for infection or malignancy, and their management in ICU has been straightforward, without any cardiovascular instability and little requirement for blood pressure support with drugs.

6.4.1 Donor-related risk

Risks to liver function

Certain donor-related factors are likely to influence the post-transplantation outcomes of their liver, including:

Age

Length of hospital stay

Length of ICU stay

Cold ischaemia time

Fatty liver

Cause of death

Donation after circulatory determination of death (DCDD).

Risk assessment of liver donors is recognised to require considerable experience in the field of liver transplantation. The Donor Risk Index (DRI), developed in Michigan, is an “integrated” measure of liver donor risk widely used in the United States.35 However, the United States DRI has been found to have poor discriminatory power when applied to European donor cohorts, and would be expected to perform similarly poorly if applied in Australia and New Zealand. Efforts are therefore underway to develop an Australian and New Zealand DRI and it is likely that this tool will be available in the next 5 years. Extra investigations may also sometimes be helpful in determining suitability for liver donation, such as CT scanning or a biopsy of a donor liver to examine the extent of steatosis (fat) in the liver (severe steatosis can pose a severe threat of a liver transplant failing to function).35 Feng S, Goodrich N, Bragg-Gresham J. Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. Am J Transplant, 2006; 6(4):783-790. ×

Use of HCV infected donor livers into HCV negative recipients

The use of HCV-positive liver donors for HCV-positive recipients is accepted practice.36 With the recent introduction of direct-acting anti-viral (DAA) therapies for HCV, yielding cure rates of greater than 95%,37,38 transplantation with a liver from an HCV-NAT positive donor might now also be considered for HCV-negative recipients who are at high risk of dying on the waiting list or delisting due to progression of liver failure or tumour.i36 Northup PG,Argo CK,Nguyen DT,McBride MA,Kumer SC,Schmitt TM,Pruett TL. Liver allografts from hepatitis C positive donors can offer good outcomes in hepatitis C positive recipients: a US National Transplant Registry analysis. Transpl Int.2010Oct;23(10):1038-44. ×37 Manns M,Samuel D,Gane EJ,Mutimer D,McCaughan G,Buti M,Prieto M,Calleja JL,Peck-Radosavljevic M,Müllhaupt B,Agarwal K,Angus P,Yoshida EM,Colombo M,Rizzetto M,Dvory-Sobol H,Denning J,Arterburn S,Pang PS,BrainardD,McHutchison JG,Dufour JF,Van Vlierberghe H,van Hoek B,Forns X;SOLAR-2 investigators. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvirplus ribavirin in patients with genotype 1 or 4 hepatitis C virus infection and advanced liver disease: a multicentre, open-label,randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis.2016 Jun;16(6):685-97. 38 Kwo PY,Mantry PS,Coakley E,Te HS,Vargas HE,Brown R Jr,Gordon F,Levitsky J,Terrault NA,Burton JR Jr,Xie W,Setze C,Badri P,Pilot-Matias T,Vilchez RA,Forns X. An interferon-free antiviral regimen for HCV after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med.2014 Dec18;371(25):2375-82. ×i No reference text available.×

However, an HCV-NAT positive donor will transmit HCV infection to the recipient, who should be treated with DAAs in the early post-transplant period.3939 Hepatitis C Virus Infection Consensus Statement Working Group. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection: a consensus statement (June 2020). Gastroenterological Society of Australia, Melbourne, 2020. ×

Issues that need to be considered when using HCV-NAT positive livers in HCV-negative recipients are listed below.

1. Possible chronic damage in HCV positive livers

Chronic HCV infection in many patients is a mild illness and HCV-positive livers are currently used in HCV-NAT positive recipients. The possibility of an HCV-positive donor liver having chronic damage from the infection requires evaluation by an experienced donor surgeon and will require frozen section biopsies.

2. Donor hepatitis C genotype

Pan genomic direct acting anti-viral drugs are so effective that HCV genotype has become less important in the allocation and possible use of an HCV-NAT positive donor liver.

3. Increased donor HIV risk

The circumstances of death in a donor actively infected with HCV may carry a small risk of transmitting HIV infection. However, this risk is mitigated by NAT testing and a good donor social history.

4. Monitoring of HCV dynamics post-transplant

Transplantation of an untreated HCV-NAT positive recipient will result in re-infection of an HCV-negative allograft within the first 24 hours post-transplant,40 and maximum replication of virus occurs somewhere between one and three months post-transplant. Recurrence of HCV is universal. The infection is more aggressive and can result in liver failure within 6-12 months.40 Shackel NA,Jamias J,Rahman W,Prakoso E,Strasser SI,Koorey DJ,Crawford MD,Verran DJ,Gallagher J,McCaughan GW.Early high peak hepatitis C viral load levels independently predict hepatitis C-related liver failure post-liver transplantation.LiverTranspl.2009 Jul;15(7):709-18. ×

Viral replication is accelerated by immunosuppression, and therefore monitoring of HCV loads in the weeks after transplantation is routine.

The genotype of a previously infected HCV-positive recipient should be checked following transplantation with an HCV-NAT positive donor liver.

i The types of recipients that might be considered for transplantation with a liver from an HCV-NAT positive donor include:i No reference text available.×

1 Patients with Fulminant Hepatic Failure

2 Patients with severe end-stage liver disease largely based on MELD score although other features of liver disease (such as encephalopathy, Hepatorenal syndrome) may justify use in patients who have been on the waiting list for a period of time without receiving donor organ.

3 Patients with low MELD scores and hepatocellular cancer where there is progression of the hepatocellular cancer (but still within transplant criteria). The use of such hepatitis C positive donors may minimise progression of HCC in this situation and withdrawal of patients from the waiting list.

4 Possible expansion to all recipients would be considered following a review of Australia and New Zealand and or international data as it becomes available (certainly within the first 12 months following introduction). ANZ data on all cases would be reported to the ANZ Liver Transplant Registry).

5. Commencing Directly Acting Antivirals (DAA) post-transplant

The Gastroenterological Society of Australia has recently published a consensus statement on the management of HCV after liver transplantation, recommending that, when possible, treatment should be initiated early after transplantation to prevent fibrosis progression. The decision to treat actively infected patients on the waiting list should be made on a case by case basis and can be commenced pre- or post-transplantation. The treatment regimen and the duration of treatment should be based on current recommendations for the treatment of compensated and decompensated cirrhotic patients.3939 Hepatitis C Virus Infection Consensus Statement Working Group. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection: a consensus statement (June 2020). Gastroenterological Society of Australia, Melbourne, 2020. ×

6. Legal issues

The risks and complications of an HCV positive organ and post-transplant anti-viral therapy need to be discussed with potential recipients to ensure informed consent is obtained. Clinicians should refer to their own jurisdictional governance and legal authorities for advice where there is a lack of clarity or policy direction in relation to informed consent.

Summary

Transplanting HCV-NAT positive livers into HCV-negative recipients has risks that need to be explicitly discussed during the consent process with potential recipients, in particular:

underestimation of liver fibrosis in the donor liver, and

the very small possibility of transmitting other infections such as HIV if the donor death occurs during the window period for this infection e.g. recent intravenous drug use.

Given the above, a HCV-NAT positive donor liver with minimal fibrosis could be transplanted safely into a consenting HCV-negative recipient with the plan to treat with DAAs as soon as practical post-transplant. The predicted cure rate of HCV infection with DAAs is currently greater than 95%; however, the risk of transplanting HCV-NAT positive donor livers into HCV-negative recipients is low but not zero. Therefore, at the present time, such donor livers can be considered for transplantation into recipients where the risk of not receiving that transplant is greater than the risk of waiting longer for another donor liver offer.

Technical considerations

There is emerging use of very small liver donors, including neonatal donors. For advice on paediatric liver donation and allocation, see Chapter 11.

With the increasing number of referrals of older potential donors, the possibility of severe vascular disease in organs from older donors is noted. On occasion, this can be so severe that the donor liver cannot be safely transplanted.

6.5 Allocation

6.5.1 General allocation principles

Given the adverse impact of longer ischaemia times on transplant outcomes, the transportation of donor livers over long distances is considered to be undesirable. Therefore, for efficiency and optimal transplant outcomes, the allocation of donor livers is organised at the level of the states and New Zealand (as opposed to binational allocation for urgently listed patients). The principle of allocation is to provide the best possible outcome for the highest priority patient on the waiting list for whom that liver would be a suitable match. Organ quality is not uniform, and therefore liver allocation must strike a balance between the expected outcomes of transplantation with a particular donor liver (i.e. benefit/utility) versus the risk of remaining on the waiting list for an unknown length of time (i.e. urgency/justice).

There are fewer problems of tissue compatibility in liver transplantation than there are for other forms of solid organ transplantation. Mismatches of HLA tissue types are of lessor relevance in liver transplantation and hence tissue crossmatching is not routinely taken into consideration. In contrast however, while liver transplantation between incompatible ABO blood groups is possible, it is a complex and higher risk undertaking (with the exception of very young children). Therefore, the first principle of liver allocation is to match donors with recipients of the same, or at least compatible, blood group. It is appreciated that there is the potential for blood group O livers, because they are universally compatible, to be allocated to recipients of other blood groups to the detriment of blood group O patients on the waiting list. All units make every effort to avoid this situation. Additionally, there is an argument in favour of transplanting blood group A subtype 2 (A2) livers into blood group O recipients (blood types A2 and O are compatible) to redress some of the inequity in allocation faced by the blood group O waitlisted population.

Other factors to be considered in liver allocation include organ size, risks of poor or delayed graft function, and hepatitis C status of the donor. Gross size discrepancy between the organ donor and the recipient may lead to situations where the donor liver is too big to be physically transplanted into the recipient or, conversely, where it is too small to support life. More difficult, however, are allocation decisions in a situation where the donor liver carries several risk factors that indicate it may not function well post-transplant. On the one hand, such a liver may prove disastrous if transplanted into a very sick recipient who would tolerate graft dysfunction poorly. On the other hand, that patient might die if they were to wait for another, hopefully better, organ. Allocation decisions are often very difficult to make but are guided by the principle of trying to provide the best possible outcome for the highest priority patient on the waiting list for whom that liver would be a suitable match.

Allocation decisions occasionally deviate from the predetermined order of waiting list priority. For example, if a unit were undertaking two liver transplants in one day, resources may be stretched and therefore the second liver may be allocated to a lower-priority patients who is anticipated to be more straight-forward surgically. Itis therefore important that allocation activity and decision-making is recorded, audited, and reviewed at the binational level. For some years, the Liver and Intestinal Transplantation Advisory Committee (LITAC) have annually reviewed allocation decisions made by all transplant jurisdictions in Australia and New Zealand. Recently, LITAC has determined that the results of this annual audit will in future be made available to the public.

6.5.2 Allocation pathway

Any liver becoming available from a deceased donor within Australia or New Zealand is first to be offered to patients listed as urgent. If there are no suitable urgent (including paediatric) candidates on the waiting list, the liver will go to the ABO blood group identical recipient with the highest clinical priority.

Often, but not always, clinical priority will align with MELD/PELD score ranking. However, there are other considerations that influence how a donor liver is allocated. The following factors may be relevant (and the reasons for the variance in allocation must be prospectively recorded):

The presence of a patient on the list with HCC

The quality of the donor liver—higher-risk donor livers may be utilised but can be problematic in patients with very high MELD scores (although it is recognised that such patients also have a higher risk of dying whilst waiting for a better liver to be offered)1–31 33rd ANZLITR Registry Report - 2021. Michael Fink and Mandy Byrne. Australia and New Zealand Liver and Intestinal Transplant Registry, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. 2 National Health and Medical Research Council (2025). Ethical guidelines for cell, tissue and organ donation and transplantation in Australia. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council. 3 Lake JR. MELD – an imperfect but thus far the best solution to the problem of organ allocation. J Gastrointestinal & Liver Dis, 2008;17(1):5–7. ×

The presence of a paediatric patient on the waiting list in need of a split or reduced-size liver, provided the donor liver is of suitable qualityiiii No reference text available.×

Donor size—overly large size discrepancies result in poor outcomes, therefore size matching may mean that the patient with the highest MELD/PELD score is not allocated a particular liver

Logistical considerations—transport, cold storage preservation time, surgeon and operating room staffs kill mix and availability, and anticipated hepatectomy time may impact on allocation decisions and result in the patients with the highest MELD/PELD score not being allocated a particular liver.

ii In the event that a donor liver is suitable for splitting between a child and an adult, it may be necessary to allocate the left-sided graft to a paediatric recipient and the right-sided graft to an adult smaller than one who would have been chosen had the liver been used whole. If there is a waiting adult patient in extremis for whom it would only be suitable to use the liver whole (rather than the small right hemigraft), then splitting may be deferred.ii No reference text available.×

6.5.3 Paediatric donor liver allocation

Paediatric organ donors comprise only approximately 5% of all organ donors in Australia and New Zealand, however there is a consensus amongst the liver transplant units in Australia and New Zealand that the allocation of these grafts involves considerations that are separate from the rest of the organ donor pool. It has been agreed that livers retrieved from donors less than 18 years old will be used for paediatric recipients. The reason for this is partly that the grieving parents of a paediatric organ donor may be comforted by knowing their child’s liver has gone to another sick child. However, this is also a situation where to do otherwise would potentially deny the possibility of finding an ideal donor for an older child (for whom it can sometimes be very difficult to find a suitably sized liver), and secondly would permit a marked donor-recipient age mismatch. In some cases, the paediatric donor liver is big enough to split into 2 grafts. In this circumstance the home state may allocate both left and right grafts to paediatric recipients on their waiting list. In the event the home state does not have a second suitable paediatric recipient, the remaining graft (either left or right) will be offered on the Paediatric Liver Allocation Rotation. In the event the split liver segment cannot be allocated to a paediatric recipient within Australia and New Zealand, the home state may allocate to an adult recipient. For detailed recommendations on paediatric liver donation and allocation, see Chapter 11.

Since the number of children awaiting liver transplant in Australia and New Zealand is low (typically less than 10 at any given point in time), it is often necessary to consider the whole list of children waiting for liver transplantation in Australia and New Zealand to achieve the goal of allocating paediatric donor livers to paediatric recipients.

6.5.4 Organ sharing and rotation

It is important that all donor livers suitable for transplantation are used. After determining that there are no urgent patients to whom a donor liver must be allocated automatically, the organ is available for allocation to the local waiting list in the jurisdiction of retrieval according to the allocation principles already described. On occasion, when no suitable local recipient can be identified, the liver will be offered on to other units around Australia and New Zealand for allocation under an agreed rotation.

6.6 Multi organ transplantation

There are patients who have multi-system diseases for whom to transplant only one organ would not improve their survival. Cystic Fibrosis (CF), for example, not only affects the lungs but also may affect the liver (as well as other body systems). Uncommonly, both the lungs and the liver may need to be transplanted for an improvement in survival to be gained.

The ethical tension that exists in multi-organ transplantation arises because one patient receives organs that could otherwise have been transplanted into two or more patients. However, to give a patient one organ when they need two (or more) is also inefficient because it may not lead to the desired improvement in survival.

Combined liver and kidney transplantation

Transplanting a kidney in conjunction with another organ is the commonest form of multi-organ transplantation. Australian eligibility criteria for combined liver-kidney transplantation are as follows:

Known end-stage kidney disease requiring dialysis

Chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis but with an estimated GFR of <30 mL/min and proteinuria of >3 g/day, or with a GFR of <20 mL/min for >3 months

Acute kidney injury (including hepatorenal syndrome) not requiring dialysis but with an estimated GFR of<25 mL/min for >6 weeks, and

Known metabolic disease including hyperoxaluria, atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome with H factor deficiency, or familial amyloidosis affecting primarily the kidney.

Patients who meet these criteria can be considered for combined liver-kidney transplantation. These criteria are concordant with those currently defined by the United States United Network for Organ Sharing.41 The decision to list a patient for a combined liver/kidney transplant should be taken after workup and assessment by, and discussion between, both the liver and renal transplant teams.41 Bloom RD and Bleicher M. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation in the MELD era. Advances Chronic Kidney Dis, 2009;16(4): 268–77. ×

6.7 Emerging issues

The landscape of liver transplantation is evolving rapidly in response to significant shifts in epidemiology, technology, and clinical practice. Several key developments are shaping current and future challenges in liver transplantation in Australia and New Zealand:

Changing Recipient Demographics and Disease Burden

There is a notable increase in the age and complexity of liver transplant candidates and recipients. This is largely due to a shift in the predominant indications for liver transplantation, with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver disease (MASLD) and Alcohol-related Liver Disease (ARLD) being the leading causes of end-stage liver disease. These patient populations often present with multiple comorbidities, necessitating more nuanced assessment, perioperative management, and long-term follow-up strategies.

Advances in Organ Preservation Technologies

The progressive implementation of machine perfusion technologies, including Hypothermic Oxygenated Machine Perfusion (HOPE) and Normothermic Machine Perfusion (NMP), is transforming donor liver assessment and preservation. These technologies offer potential benefits such as extended preservation times, viability assessment, and improved utilisation of marginal or extended criteria donors. Transplant units across Australia and New Zealand are at varying stages of adopting these technologies, and national data collection and collaborative evaluation efforts are critical to guiding best practice and policy development.

Internationally, the use of Normothermic Regional Perfusion (NRP) is having dramatic impacts by safely expanding the donor pool by permitting utilisation of organs that would previously not have been able to be used. Such an advance is yet to be introduced in Australia and New Zealand.

The Rise of Transplant Oncology

Liver transplantation for selected malignancies is becoming increasingly accepted, representing a paradigm shift in transplant candidacy. Conditions that were historically considered absolute contraindications—such as colorectal liver metastases and unresectable cholangiocarcinoma—are now being reconsidered under strict selection criteria and within clinical trials or protocolised programs. This emerging field of transplant oncology necessitates careful ethical and clinical scrutiny, equitable access considerations, and close monitoring of outcomes to ensure appropriate patient selection and optimal graft use.