7 Lung

7.1 Preamble

Lung transplantation is a highly effective treatment for advanced lung disease. Generally, a 60% five-year and 40% ten-year survival rate is expected following lung transplantation as per the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) registry report.1 However, only approximately one in twenty of those individuals with severe lung disease who might benefit from a lung transplant will actually receive one.1,21 Perch M, Hayes D, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-ninth adult lung transplantation report-2022; focus on lung transplant recipients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022 Oct;41(10):1335-1347. ×1 Perch M, Hayes D, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-ninth adult lung transplantation report-2022; focus on lung transplant recipients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022 Oct;41(10):1335-1347. 2 Chambers DC, Perch M, Zuckermann A, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1060-1072. ×

Due to the scarcity of donor lungs, lung transplantation should be considered for patients with chronic end-stage lung disease who have a two-year likelihood of survival predicted at less than 50% without transplantation3 and who have no alternative treatment options. Infant lung transplants (currently not available in Australia and New Zealand) and living-related lung transplants have their own specific issues and are not discussed in this document. Information pertaining to peadiatric lung donation can be found in Section 11.4.3 Leard LE, Holm AM, Valapour M, et al. Consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: An update from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Nov;40(11):1349-1379. ×

Lung transplantation is a complex therapy with significant risks, and therefore the careful evaluation of all organ systems (with appropriate specialist advice as needed) is a mandatory part of the assessment to evaluate a potential patient’s risk of short and long-term morbidity and mortality post-transplantation. As significant contraindications may exist, it follows that not all potential recipients will prove suitable for lung transplantation.22 Chambers DC, Perch M, Zuckermann A, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1060-1072. ×

It is also possible that, even after active listing for lung transplantation, an individual may subsequently develop a new complication or become too frail to successfully undergo transplantation. In this circumstance, an individual may then be delisted temporarily (if the situation can be resolved) or permanently (if the condition is unresolvable). Intensive interventions such as mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be used to provide a short-term ‘bridge’ to lung transplantation, but these are complex therapies that can themselves be associated with patient deterioration to the extent that ultimately transplantation may not be feasible.

The ISHLT guidelines on patient eligibility and selection for lung transplantation were revised in 2021 with input from Australia and New Zealand clinicians. Australian and New Zealand lung transplant units follow the recommendations contained within these guidelines.2,32 Chambers DC, Perch M, Zuckermann A, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1060-1072. 3 Leard LE, Holm AM, Valapour M, et al. Consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: An update from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Nov;40(11):1349-1379. ×

7.1.1 Ethical Principles for the Allocation of Donor Lungs

Utility: To maximise net benefit (e.g., using years of survival gained to prioritise allocation)

Justice: To distribute the benefits and burdens of organ allocation system in a fair way (e.g., using medical urgency to prioritise allocation, allowing special consideration for candidates for whom it is difficult to find a suitable organ)

Respect for persons: To treat persons as autonomous with the righ

7.2 Recipient eligibility criteria

Early referral for lung transplant assessment is recommended to optimise time for thorough evaluation of the inclusion criteria outlined below in 7.2.1, especially for interstitial lung disease patients whose referral for transplant assessment should occur at the time of diagnosis. Early referral helps to facilitate transplant education for patients and their caregivers as well as allowing time to address barriers to transplant, which may include obesity, physical frailty, malnutrition, or inadequate social supports, with pre-transplantation therapy. On referral to lung transplant units, simultaneous referral to palliative care services is highly recommended to support the patient’s journey through transplant assessment, potential waitlisting, lung transplantation surgery, and their post-transplant life.

7.2.1 Inclusion criteria

Indications for lung transplantation are:

Progressive respiratory failure despite optimal medical, interventional and surgical treatment, and/or

Poor quality of life, potentially with intractable symptoms and repeated hospital admissions (e.g. New York Heart Association [NYHA] Class III-IV).

Additional disease-specific candidate selection criteria at time of listing

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease:

Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1 ) <25 % predicted • Body-mass, airflow obstruction, dyspnea and exercise (BODE) index ≥7

Clinical deterioration: severe exacerbation with hypercapnoic respiratory failure or recurrent exacerbations despite maximal treatment, pulmonary rehabilitation, and oxygen therapy

Moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension

Chronic hypercapnia.

Cystic Fibrosis:

FEV₁ <30% predicted especially if a rapid downward trajectory is observed (<40% predicted in children)

Frequent hospitalisation, (>28 days/year) despite optimal medical therapy i.e., trial of elexacaftor/ tezacaftor/ivacaftor

Massive haemoptysis (>240ml) despite bronchial artery embolization

Pneumothorax

Exacerbations requiring non-invasive ventilation and/or intravenous antibiotics

6-minute walk test <400m

Worsening nutritional status despite nutritional interventions (BMI <18kg/m²)

Development of pulmonary hypertension (PASP >50mmHg or RV dysfunction)

PCO₂ >50 mmHg and/or PO₂ <60 mmHg.

Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD):

Any form of pulmonary fibrosis with forced vital capacity (FVC) of <80% predicted or diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) <40% predicted

Decline in FVC of >10% or decline in DLCO > 10% within the prior 6 months

Supplementary oxygen requirement at rest and/or exertion

Development of pulmonary hypertension demonstrated by echo or right-heart catheter

Hospitalisation because of respiratory decline, acute exacerbation, or pneumothorax

Desaturation to < 88% on 6 minute walk test or >50 m decline in 6 minute walk test distance in the past 6 months

Inflammatory ILD – progressive decline of pulmonary function with radiographic progression despite treatment

For patients with connective tissue disease or familial pulmonary fibrosis, early referral is recommended as extrapulmonary manifestations may require special consideration.

Pulmonary vascular diseases:

NYHA Functional class III or IV/REVEAL risk score >10 despite escalation of pulmonary vasodilator therapy

Progressive hypoxemia

Significant right ventricle dysfunction despite pulmonary hypertension (PAH) therapy

Secondary organ decline due to PAH i.e., kidney, liver.

Known or suspected high-risk variants such as Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease/Pulmonary capilliary hemangiomatosis (PVOD/PCH), scleroderma or large pulmonary artery aneurysms

Life-threatening complications such as: hemoptysis.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM)

FEV1 <30% predicted + diseases progression despite mTOR inhibitor therapy

NYHA Class III or IV

Hypoxemia at rest

Pulmonary Hypertension

Refractory Pneumothorax.

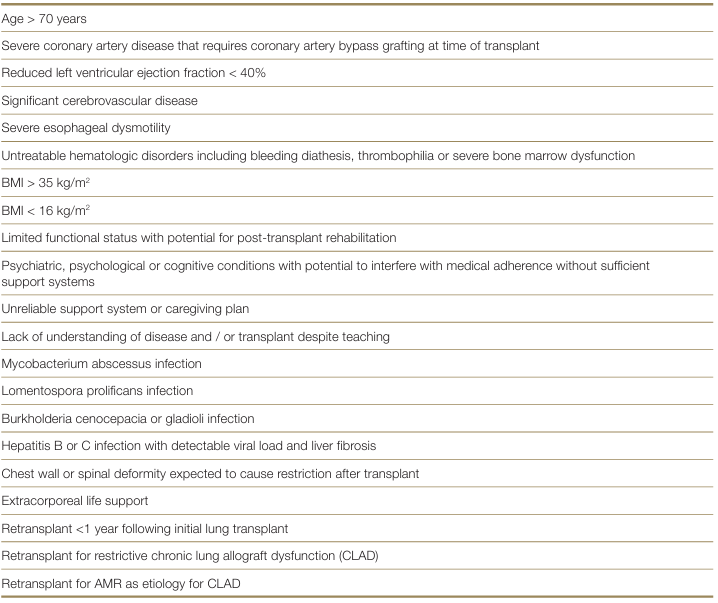

7.2.2 Exclusion criteria

Absolute contraindications to lung transplantation include any condition or combination of conditions that result in an unacceptably high risk of mortality or morbidity, limiting the likely survival benefit from transplantation or the predicted gain in quality of life. Absolute contraindications include (but are not limited to):2–82 Chambers DC, Perch M, Zuckermann A, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1060-1072. 3 Leard LE, Holm AM, Valapour M, et al. Consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: An update from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Nov;40(11):1349-1379. 4 Barbour KA, Blumenthal JA and Palmer SM. Psychosocial issues in the assessment and management of patients undergoing lung transplantation. Chest, 2006; 129(5): 1367–74. 5 Dew AM, DiMartini AF, Dobbels F et al. The 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW recommendations for the psychosocial evaluation of adult cardiothoracic transplant candidates and candidates for long-term mechanical circulatory support, The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, 2018; 31 (7): 803-823. 6 Denhaerynck K, Desmyttere A, Dobbels F, et al. Nonadherence with immunosuppressive drugs: U.S. compared with European kidney transplant recipients. Prog Transplant, 2006; 16(3): 206–14. 7 Dobbels F, Verleden G, Dupont L, et al. To transplant or not? The importance of psychosocial and behavioural factors before lung transplantation. Chron Respir Dis, 2006; 3(1): 39–47. 8 Hayanga AJ, Aboagye JK, Hayanga HE, et al. Contemporary analysis of early outcomes after lung transplantation in the elderly using a national registry. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:182-8. ×

Risk factors with high or substantially increased risk of adverse patient outcome post lung transplantation.

Candidates with these risk factors may be considered in some transplant units with specific expertise3, it is likely that the presence of multiple comorbidities alongside low physiologic reserve in patients over 70 years of age will exclude many of such patients from consideration for lung transplantation.3 Leard LE, Holm AM, Valapour M, et al. Consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: An update from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Nov;40(11):1349-1379. ×

7.2.3 Retransplantation

Retransplantation may be an appropriate consideration in select candidates should an individual deteriorate after receiving a lung transplant and re-qualifies for waitlisting according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria stated above. Evaluation of retransplantation should explore possible reasons for graft failure, rate of deterioration, donor lung availability and the management of patient’s sensitisation/potential high panel-reactive antibody.

7.3 Waiting list management

Lung transplant units will generally review patients listed for lung transplantation every 4-8 weeks in an outpatient clinic. This ongoing reassessment is critical to evaluate the patient’s changing status against predicted peri-operative or post-transplant outcomes. Repetition of some assessments such a physical frailty, CT Chest imaging and serum nicotine/cotinine levels may be required by transplant units to ensure waitlisted patients still meet eligibility criteria for transplantation.

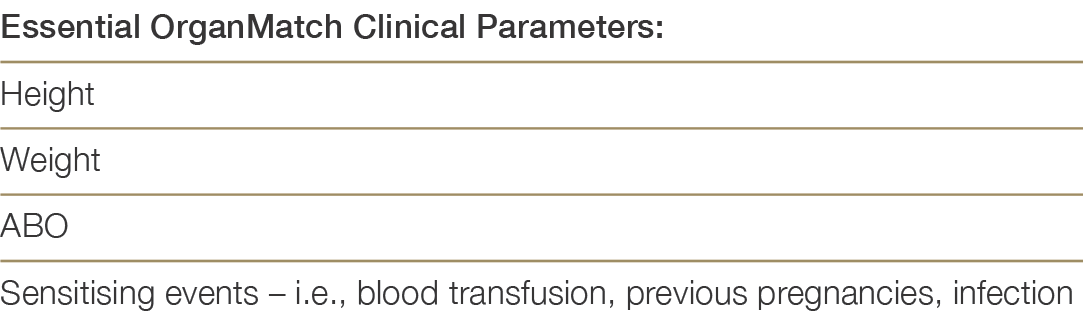

Patients eligible for the transplant waiting list (TWL) must be registered in OrganMatch, in the Lung- TWL program. Initial collection of samples is required for Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) typing and identification of HLA antibodies using solid phase technique (Luminex). Samples are collected monthly, and HLA antibody testing will be performed every three months. Clinical parameters required for the Organmatch Lung algorithm, must be entered in OrganMatch by the clinical or transplant unit at the time of listing. Table 7.0 shows the relevant clinical parameters.

Table 7.0: Clinical Parameters required for OrganMatch Lung Transplant waitlisting and algorithm

7.3.1 Urgent patients

Although there is no defined national priority/urgent lung listing category, under some circumstances a lung transplant waitlisted patient from one state may be notified to other state Lung Transplant Programmes in an attempt to increase their opportunities for lung allocation and transplantation. This process is termed National Notification. Urgent patients are incorporated into the lung matching algorithm described in Section 7.5.2 and are offered deceased donor lungs as per the TSANZ-OTA National Standard Operating Procedure: Organ Allocation, Organ Rotation, Urgent Listing, also described in Appendix F. National notification for lung transplantation is at the discretion of the Lung Transplant Unit Director. It is the responsibility of the Lung Transplant Director (or their delegate) to notify all other Lung Transplant Units. Updating the recipients OrganMatch enrolment must occur to ensure appropriate identification and matching. The listing can be viewed within OrganMatch by the donation and transplant clinicians as required.

7.3.2 Paediatric patients

The nationally funded centre for paediatric lung transplantation resides at the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, Victoria, with a recommended age range for referral from four to sixteen years.

7.3.3 Histocompatibility Assessment

Each recipient must undergo a series of tests performed at the state Tissue Typing laboratories. These include:

HLA typing using molecular technique such as Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) at the following HLA loci: A, B, C, DRB1, DQB1, DQA1, DPB1, DPA1,

HLA antibody screening using Luminex single antigen beads. This screening must have occurred within 120 days to be included in matching. It is optimal that all waitlisted patients are screened every 3 months.

These tests will be used in the histocompatibility assessment by the Tissue Typing labs and in consultation with the clinical unit to assign unacceptable antigens. These assigned unacceptable antigens can assist in excluding a waitlisted patient from incompatible donor offers. Additional comprehensive information is available within the National Histocompatibility Guidelines: https://tsanz.com.au/storage/Guidelines/TSANZ_ NationalHistocompatibilityAssessmentGuidelineForSolidOrganTransplantation_04.pdf

7.4 Donor assessment

7.4.1 Donor-related risk

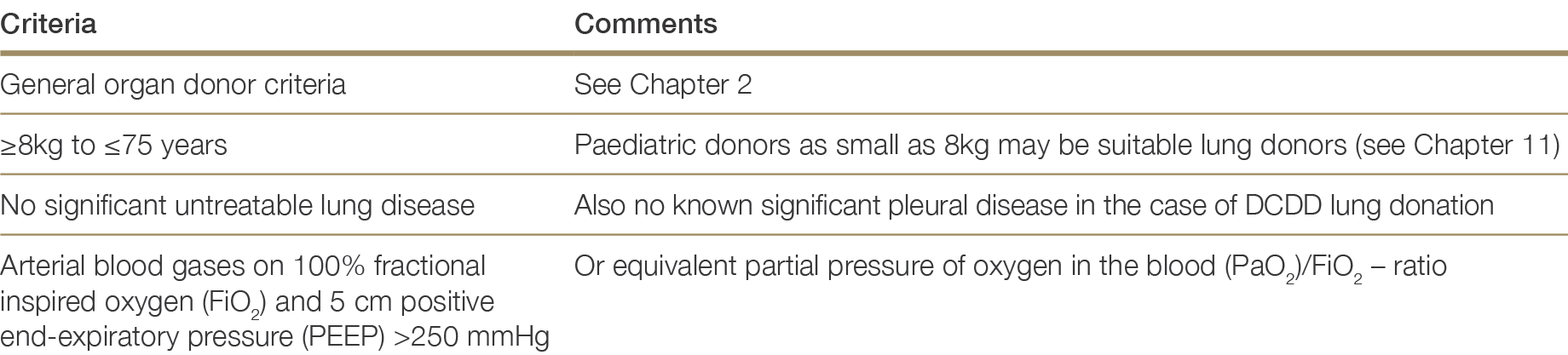

Table 7.1 outlines standard criteria for lung donation. Historically, approximately 35-40% of deceased donor lungs offered for donation in Australia and New Zealand have been considered acceptable for clinical transplantation.11 This compares with international retrieval rates of only 15-20%.12,13,14 Specific management protocols have evolved for the potential lung donor that address common scenarios such as retained secretions, aspiration, ventilator-associated pneumonia, barotrauma prevention, atelectasis and neurogenic pulmonary oedema. A higher-risk lung donor is one who has characteristics that may adversely influence the early and/or long-term transplant outcomes of the chosen recipient. Traditionally, a higher-risk donor has been defined as possessing one of the following characteristics: age >60 years, smoking history >20 pack years, PaO2 <300 mmHg, chest x-ray positive for infiltrates or trauma, persistent purulent secretions at bronchoscopy or prolonged ischaemic time. Nonetheless, many potential donors with these characteristics will prove suitable for lung donation following careful organ assessment and retrieval.15–23 The evolution of ex-vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) will further enhance acceptance rates for lung donation especially those donors considered very high risk or with multiple risk factors. The EVLP system consists of a perfusion circuit with tubing and a reservoir, enabling lungs to be sustained ex-vivo at normal temperature with an extracellular perfusate rich in human albumin to maintain high colloid pressure. The principles of EVLP are to reduce interstitial oedema within the donated lung and to perform maneuvers to facilitate alveolar recruitment, whilst monitoring the trajectory of key physiological measures including PO2, pulmonary vascular resistance and lung compliance.11 ANZOD Registry. 2022 Annual Report, Section 8: Deceased Donor Lung Donation. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2022. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au ×12 Reyes KG, Mason DP, Thuita L, et al. Guidelines for donor lung selection: time for revision? Ann Thorac Surg, 2010;89(6):1756-64. 13 Botha P, Trivedi D, Weir CJ, et al. Extended donor criteria in lung transplantation: impact on organ allocation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2006;131(5):1154-60. 14 Van der Mark SC, Rogier A.S. Hoek, Merel E. Hellemons Developments in lung transplantation over the past decade. European Respiratory Review Sep 2020, 29 (157) 190132; Bittle GJ, Sanchez PG, Kon ZN, et al. The use of lung donors older than 55 years: a review of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2013; 32 (8): 760-768. ×15 Bittle GJ, Sanchez PG, Kon ZN, et al. The use of lung donors older than 55 years: a review of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2013; 32 (8): 760-768.16 Schiavon M, Falcoz PE, Santelmo N, et al. Does the use of extended criteria donors influence early and long term results of lung transplantation? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg, 2012; 14 (2): 183-7. 17 Zych B, Garcia-Saez D, Sabashnikov A, et al. Lung transplantation from donors outside standard acceptability criteria – are they really marginal? Transpl Int, 2014; 27 (11): 1183-91. 18 Copeland H, Hayanga JWA, Neyrinck A, MacDonald P, et al. Donor heart and lung procurement: A consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 Jun;39(6):501-517. 19 Kotecha S, Hobson J, Fuller J, et al. Continued Successful Evolution of Extended Criteria Donor Lungs for Transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017 Nov;104(5):1702-1709. Botha P, Rostron AJ, Fisher AJ, et al. Current strategies in donor selection and management. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2008; 20(2): 143–51. 20 Botha P, Rostron AJ, Fisher AJ, et al. Current strategies in donor selection and management. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2008; 20(2): 143–51.21 Snell GI, Westall GP, Oto T. Donor risk prediction: how ‘extended’ is safe? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013 Oct;18(5):507-12. 22 Orens JB, Boehler A, de Perrot M, et al. A review of lung transplant donor acceptability criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2003; 22(11): 1183–200. 23 Snell GI, Westall GP. Selection and management of the lung donor. Clin Chest Med. 2011 Jun;32(2):223-32. ×

Table 7.1: Suitability criteria for lung donation23,2423 Snell GI, Westall GP. Selection and management of the lung donor. Clin Chest Med. 2011 Jun;32(2):223-32. 24 Van Raemdonck D, Neyrinck A, Verleden GM, et al. Lung donor selection and management. Proc Am Thorac Soc, 2009; 6(1): 28–38. Snell GI, Esmore DS, Westall GP, et al. The Alfred Hospital lung transplant experience. Clin Transpl 2007: 131–44. ×

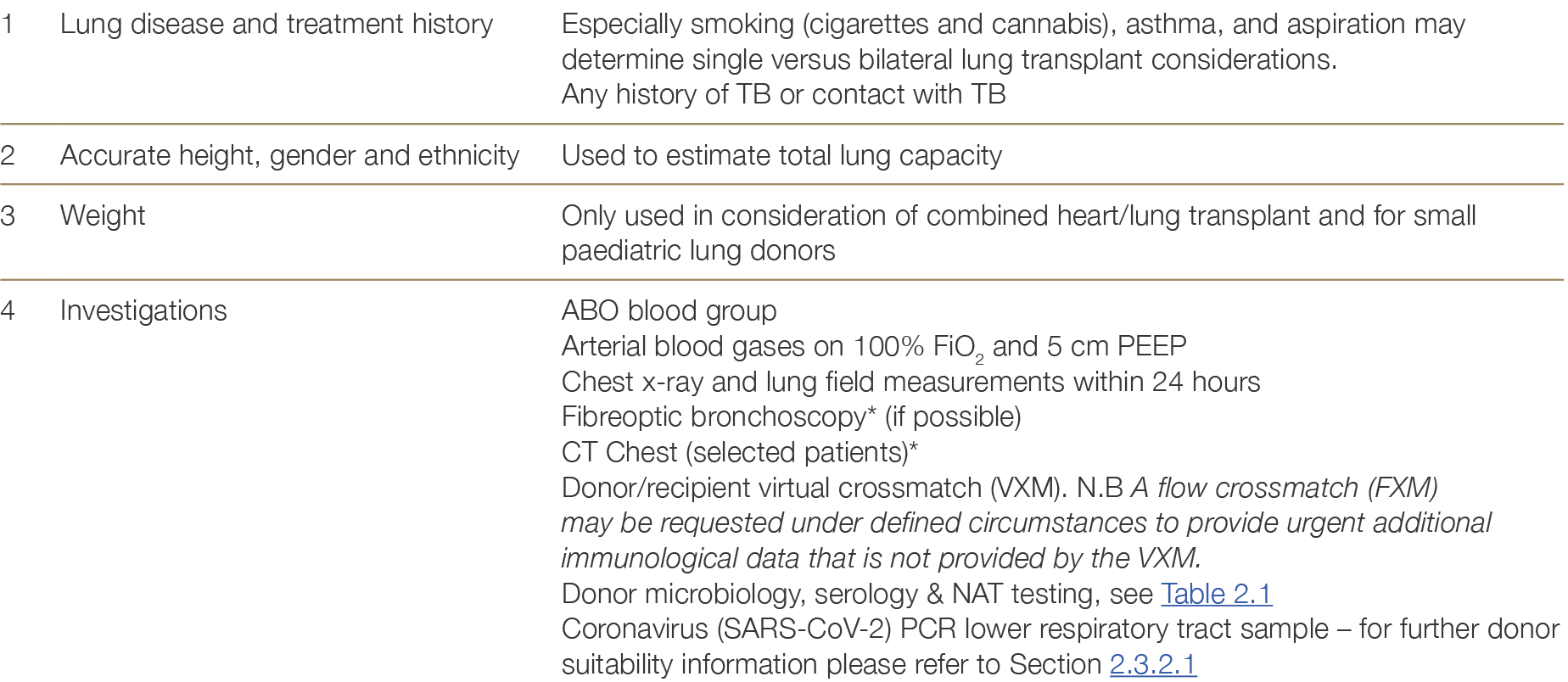

7.4.2 Donor information and testing

Table 7.2: Donor information required for lung allocation

* See Appendix E. Ante mortem interventions such as lung bronchoscopy and CT Chest are commonly deployed in all jurisdictions with minor variations between states and, in some jurisdictions, between hospitals.

7.5 Allocation

7.5.1 General allocation principles

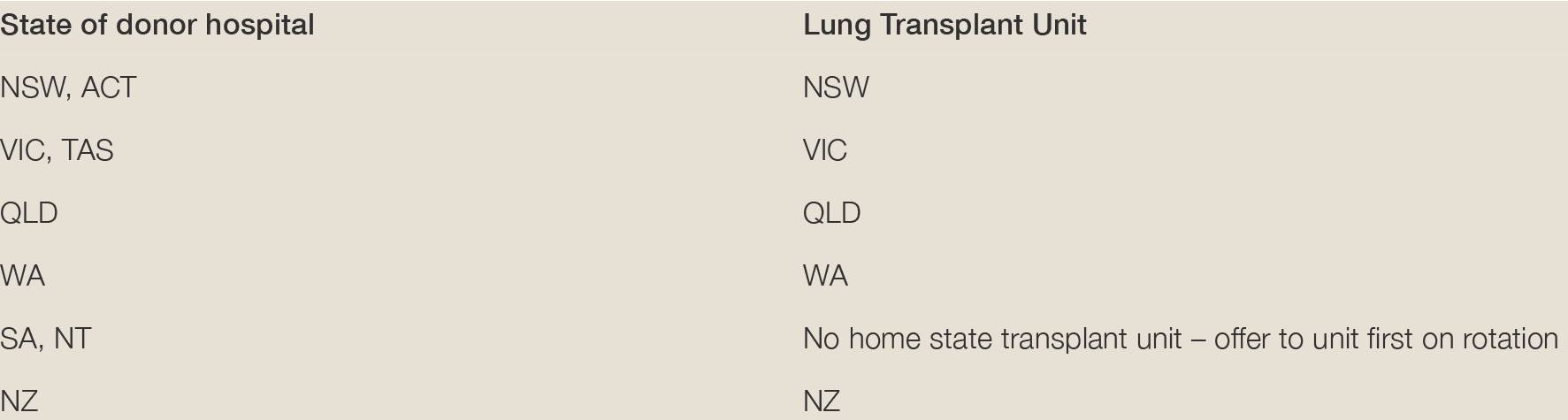

The lung transplant unit in the home state receives the donor offer as detailed below and given 30 minutes to respond to the offer. If the home state lung transplant unit declines the offer, the donation offer is made on rotation to non-home state lung transplant units – with a 30-minute response time, as per the TSANZ-OTA National Standard Operating Procedure – Organ Allocation, Organ Rotation, Urgent Listing.

The acceptance of lungs by a transplant unit depends on a large variety of technical and logistic factors, including the existence of a suitable recipient (see Table 7.3). Although it is known that a variety of factors may manifest as apparent donor lung ‘quality’ (and be measured as oxygenation, chest X-ray abnormalities and bronchoscopy findings), no specific higher-risk donor category is used when allocating lungs or making acceptance decisions.

7.5.2 Lung Matching Algorithm

Considerable logistical issues and the various combinations of potential lung and/or heart transplantation that heart and lung transplant units must consider when donor organs are offered add complexity to the development of a lung matching algorithm.25–2725 Snell GI, Esmore DS, Westall GP, et al. The Alfred Hospital lung transplant experience. Clin Transpl 2007: 131–44.26 Snell GI, Griffiths A, Macfarlane L, et al. Maximizing thoracic organ transplant opportunities: the importance of efficient coordination. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2000; 19(4): 401–07. 27 Orens JB and Garrity ER, Jr. General overview of lung transplantation and review of organ allocation. Proc Am Thorac Soc, 2009; 6(1): 13–19. ×

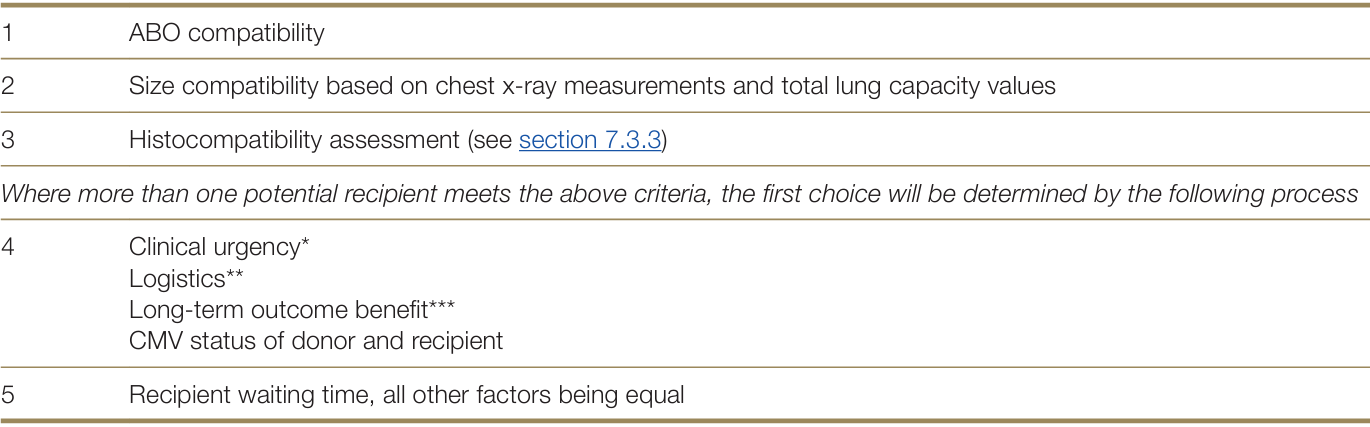

The OrganMatch Lung TWL matching algorithm uses blood group compatibility, size matching and immunological compatibility to generate a list of potential recipients. The tissue typing laboratory will perform virtual crossmatches (VXM) on the recipients on the waitlist. Patients with unacceptable antigens to the donor HLA typing will be excluded from the match. Whilst OrganMatch enhances the process of recipient matching, the final allocation decision is always at the discretion of the accepting lung transplant unit. Further information on OrganMatch and the lung matching algorithm can be found here: https://www.donatelife.gov.au/for-healthcare-workers/organmatch/training-hub#Transplantation_Portal

For allocation of lungs from paediatric donors, please refer to Section 11.4.

Table 7.3: Individual patient allocation criteria for donor lungs

Notes:

* Clinical urgency: Graded by level of support required and evidence of rapidity of deterioration of underlying indication for transplant. Level of support includes, but not limited to the following:

— Extracorporeal membrane oxygenator (ECMO)

— Invasive mechanical ventilation

— Non-invasive ventilation

— High-flow O2 requirement

— Low-flow O2 requirement

— Prolonged or recurrent hospitalisation

— Other support devices such as continuous intravenous therapies.

Rapidity of deterioration includes, but not limited to

— Change in NYHA functional Class or Medical Research Council(MRC) grade

— Significant fall in lung function parameters

— Significant fall in PaO2

— Significant rise in partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the blood (PaCO2)

— Significant fall in 6-minute walk test distance

— Need for escalation in level of support as above

— Time course of progression of radiological changes

— Development of symptomatic pulmonary hypertension

— Development of refractory right heart failure.

** Logistical considerations include: operation type (lobar, single, bilateral, heart/lung); availability of required team members for the retrieval, lung transplant(s) and related cardiac transplants (paired donor heart or domino heart transplant); timely availability of all recipients; coordination between all involved transplant units arranging and performing the transplant procedures.

***Consideration of long-term outcome benefit includes: Comorbidities such as osteoporosis, gastroesophageal reflux, known coronary or peripheral vascular disease, carriage of pan-resistant organisms, poor rehabilitation potential, history of malignancy, advanced age, lack of compliance, morbid obesity or malnutrition and other relative contraindications for lung transplantation which have been shown to be associated with an inferior outcome benefit.

7.6 Multi-organ transplantation

Patients with respiratory failure and concurrent disease of another solid organ—typically heart, kidney, or liver—may be considered for combined organ transplantation. The general eligibility criteria for multi-organ transplantation follow the individual eligibility criteria for each organ to be transplanted. Multi-organ transplant is a more complicated surgical procedure with associated unique medical and other post-operative complications. As such, it is recommended for younger patients with functional reserve and with an ability to withstand the heightened surgical risks and prolonged rehabilitation associated with this complicated procedure. Referral for consideration of multi-organ transplantation should occur earlier in the disease course in alignment with expected longer waitlisted time.33 Leard LE, Holm AM, Valapour M, et al. Consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: An update from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Nov;40(11):1349-1379. ×

7.7 Emerging Issues

Utilisation of Hepatitis C donors(28-31)1 Perch M, Hayes D, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-ninth adult lung transplantation report-2022; focus on lung transplant recipients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022 Oct;41(10):1335-1347. 2 Chambers DC, Perch M, Zuckermann A, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1060-1072. 3 Leard LE, Holm AM, Valapour M, et al. Consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: An update from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Nov;40(11):1349-1379. 4 Barbour KA, Blumenthal JA and Palmer SM. Psychosocial issues in the assessment and management of patients undergoing lung transplantation. Chest, 2006; 129(5): 1367–74. 5 Dew AM, DiMartini AF, Dobbels F et al. The 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW recommendations for the psychosocial evaluation of adult cardiothoracic transplant candidates and candidates for long-term mechanical circulatory support, The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, 2018; 31 (7): 803-823. 6 Denhaerynck K, Desmyttere A, Dobbels F, et al. Nonadherence with immunosuppressive drugs: U.S. compared with European kidney transplant recipients. Prog Transplant, 2006; 16(3): 206–14. 7 Dobbels F, Verleden G, Dupont L, et al. To transplant or not? The importance of psychosocial and behavioural factors before lung transplantation. Chron Respir Dis, 2006; 3(1): 39–47. 8 Hayanga AJ, Aboagye JK, Hayanga HE, et al. Contemporary analysis of early outcomes after lung transplantation in the elderly using a national registry. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:182-8. 9 Yanis A, Haddadin Z, Spieker AJ, et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses to the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine among a cohort of solid organ transplant recipients and healthy controls. Transpl Infect Dis. 2022 Feb;24(1):e13772. Schramm R, Costard-Jäckle A, Rivinius R, et al. Poor humoral and T-cell response to two-dose SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccine BNT162b2 in cardiothoracic transplant recipients. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021 Aug;110(8):1142-1149. 10 Schramm R, Costard-Jäckle A, Rivinius R, et al. Poor humoral and T-cell response to two-dose SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccine BNT162b2 in cardiothoracic transplant recipients. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021 Aug;110(8):1142-1149.11 ANZOD Registry. 2022 Annual Report, Section 8: Deceased Donor Lung Donation. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2022. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au 12 Reyes KG, Mason DP, Thuita L, et al. Guidelines for donor lung selection: time for revision? Ann Thorac Surg, 2010;89(6):1756-64. 13 Botha P, Trivedi D, Weir CJ, et al. Extended donor criteria in lung transplantation: impact on organ allocation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2006;131(5):1154-60. 14 Van der Mark SC, Rogier A.S. Hoek, Merel E. Hellemons Developments in lung transplantation over the past decade. European Respiratory Review Sep 2020, 29 (157) 190132; Bittle GJ, Sanchez PG, Kon ZN, et al. The use of lung donors older than 55 years: a review of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2013; 32 (8): 760-768. 15 Bittle GJ, Sanchez PG, Kon ZN, et al. The use of lung donors older than 55 years: a review of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2013; 32 (8): 760-768.16 Schiavon M, Falcoz PE, Santelmo N, et al. Does the use of extended criteria donors influence early and long term results of lung transplantation? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg, 2012; 14 (2): 183-7. 17 Zych B, Garcia-Saez D, Sabashnikov A, et al. Lung transplantation from donors outside standard acceptability criteria – are they really marginal? Transpl Int, 2014; 27 (11): 1183-91. 18 Copeland H, Hayanga JWA, Neyrinck A, MacDonald P, et al. Donor heart and lung procurement: A consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 Jun;39(6):501-517. 19 Kotecha S, Hobson J, Fuller J, et al. Continued Successful Evolution of Extended Criteria Donor Lungs for Transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017 Nov;104(5):1702-1709. Botha P, Rostron AJ, Fisher AJ, et al. Current strategies in donor selection and management. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2008; 20(2): 143–51. 20 Botha P, Rostron AJ, Fisher AJ, et al. Current strategies in donor selection and management. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2008; 20(2): 143–51.21 Snell GI, Westall GP, Oto T. Donor risk prediction: how ‘extended’ is safe? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013 Oct;18(5):507-12. 22 Orens JB, Boehler A, de Perrot M, et al. A review of lung transplant donor acceptability criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2003; 22(11): 1183–200. 23 Snell GI, Westall GP. Selection and management of the lung donor. Clin Chest Med. 2011 Jun;32(2):223-32. 24 Van Raemdonck D, Neyrinck A, Verleden GM, et al. Lung donor selection and management. Proc Am Thorac Soc, 2009; 6(1): 28–38. Snell GI, Esmore DS, Westall GP, et al. The Alfred Hospital lung transplant experience. Clin Transpl 2007: 131–44. 25 Snell GI, Esmore DS, Westall GP, et al. The Alfred Hospital lung transplant experience. Clin Transpl 2007: 131–44.26 Snell GI, Griffiths A, Macfarlane L, et al. Maximizing thoracic organ transplant opportunities: the importance of efficient coordination. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2000; 19(4): 401–07. 27 Orens JB and Garrity ER, Jr. General overview of lung transplantation and review of organ allocation. Proc Am Thorac Soc, 2009; 6(1): 13–19. 28 Aslam S, Grossi P, Schlendorf KH, Holm AM, Woolley AE, Blumberg E, Mehra MR; working group members. Utilization of hepatitis C virus-infected organ donors in cardiothoracic transplantation: An ISHLT expert consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 May;39(5):418-432. 29 Woolley AE, Baden LR. Increasing access to thoracic organs from donors infected with hepatitis C: A previous challenge-now an opportunity. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 May;37(5):681-683. Schlendorf KH, Zalawadiya S, Shah AS, et al. Early outcomes using hepatitis C-positive donors for cardiac transplantation in the era of effective direct-acting anti-viral therapies. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Jun;37(6):763-769. 30 Schlendorf KH, Zalawadiya S, Shah AS, et al. Early outcomes using hepatitis C-positive donors for cardiac transplantation in the era of effective direct-acting anti-viral therapies. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Jun;37(6):763-769.31 Woolley AE, Singh SK, Goldberg HJ et al. DONATE HCV Trial Team. Heart and Lung Transplants from HCV-Infected Donors to Uninfected Recipients. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 25;380(17):1606-1617. ×

The increasing availability of direct acting anti-viral (DAA) therapies for successful treatment of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) has allowed the cardiothoracic transplant community to now consider the use of HCV-positive donors for lung transplantation.28–31 The opportunity to safely expand the donor pool and potentially reduce the time on waitlist by accepting HCV-positive donors requires careful management pre and post transplantation. These management recommendations include but are not limited to:28 Aslam S, Grossi P, Schlendorf KH, Holm AM, Woolley AE, Blumberg E, Mehra MR; working group members. Utilization of hepatitis C virus-infected organ donors in cardiothoracic transplantation: An ISHLT expert consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 May;39(5):418-432. 29 Woolley AE, Baden LR. Increasing access to thoracic organs from donors infected with hepatitis C: A previous challenge-now an opportunity. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 May;37(5):681-683. Schlendorf KH, Zalawadiya S, Shah AS, et al. Early outcomes using hepatitis C-positive donors for cardiac transplantation in the era of effective direct-acting anti-viral therapies. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Jun;37(6):763-769. 30 Schlendorf KH, Zalawadiya S, Shah AS, et al. Early outcomes using hepatitis C-positive donors for cardiac transplantation in the era of effective direct-acting anti-viral therapies. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Jun;37(6):763-769.31 Woolley AE, Singh SK, Goldberg HJ et al. DONATE HCV Trial Team. Heart and Lung Transplants from HCV-Infected Donors to Uninfected Recipients. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 25;380(17):1606-1617. ×

Patient education and associated informed consent specific to high viral risk donors prior to listing, and at time of transplantation

Availability and assessment of waitlisted patient’s recent serology i.e., pre-existing HBV infection

Careful pharmacological evaluation of drug interactions before initiation of DAAs to reduce decreased efficacy of HCV treatment

Patient’s ability to adhere with DAA medication protocol and prevent potential further HCV transmission

Patient’s ability to comply to surveillance monitoring of HCV RNA post transplantation as per transplant unit policy.

The ISHLT Consensus Statement on utilisation of hepatitis C virus-infected organ donors in cardiothoracic transplantation28 provides; further management considerations, guidance on recommended surveillance schedule, and a potential DAA treatment strategy when utilising HCV-positive organs for cardiothoracic transplantation into HCV-negative recipients.28 Aslam S, Grossi P, Schlendorf KH, Holm AM, Woolley AE, Blumberg E, Mehra MR; working group members. Utilization of hepatitis C virus-infected organ donors in cardiothoracic transplantation: An ISHLT expert consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 May;39(5):418-432. ×