10 Vascularised composite allotransplantation

10.1 Preamble

Vascularised composite allotransplantation (VCA) is the transplantation of a vascularised body part containing multiple tissue types as an anatomical/structural unit. VCA is fundamentally more similar to organ transplantation than to tissue transplantation, and is recognised as such by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, and by the European Parliament.1 Body parts that meet the definition of VCA include limbs, face, larynx and abdominal wall.1 Rahmel A. Vascularized Composite Allografts: Procurement, Allocation, and Implementation. Curr Transplant Rep, 2014;1(3):173-182. ×

As this is such a new field, protocols for assessing recipient and donor eligibility for VCA are currently developed and applied at the institutional level. Efforts are underway to generate standard international guidelines for recipient and donor eligibility for VCA, with a particular focus on developing standardised psychosocial assessment tools (the ‘Chauvet protocol’). 2 However, these efforts are limited by the small number of VCA transplants that have been performed to date worldwide, and hence the small size and heterogeneity of the available cohort from which to draw evidence-based guidelines. As the practice of VCA transplantation matures, the capacity to generate internationally standardised, evidence-based guidelines will increase.2 Kumnig M, Jowsey SG, Moreno E, et al. An overview of psychosocial assessment procedures in reconstructive hand transplantation. Transplant International, 2014;27(5):417-27. ×

10.2 Recipient eligibility criteria: hand transplantation

Criteria for recipient eligibility for VCA have a number of unique considerations compared to other forms of transplantation:

The recipient will experience both positive and negative changes to body image: the graft—and therefore rejection—is visible

Risk of death or return to dialysis are not factors motivating adherence to immunosuppression

VCA transplantation may decrease rather than increase life expectancy—the goal is not to extend life, but to increase quality of life

The recipient is required to comply with lengthy and intensive rehabilitation to achieve function from their transplant, and may initially experience increased disability and/or a decrement in quality of life; for some patients, the only gain will be with respect to body image—there may be no functional gain. All patients should be advised of the potential risk of a worse outcome, including the possibility of graft explant.

10.2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 10.1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria for hand transplantation

Inclusion criteria

Bilateral loss of hands/forearm or unilateral loss with significant contralateral dysfunction as a result of trauma/illness >1 year ago

Patient aged 18 years or older

Psychologically well and stable, including the ability to form a therapeutic alliance with the transplant team *

Able to understand the complexity of the procedure, as well as the risks, benefits and alternatives, and able to communicate their informed decision

A reasonable post-transplant life expectancy, defined as an 80% likelihood of surviving for at least five years after transplantation

Exclusion criteria

Significant uncorrected chronic comorbid disease, e.g. cardiovascular, respiratory or kidney disease, which results in undue risk from anaesthetic or immunosuppression

Active chronic infection

Active malignancy or one with high five-year likelihood of recurrence

Congenital abnormalities of limbs

Proximal amputation and/or proximal neuromuscular dysfunction

Inability to comply with long term, complex medical and rehabilitative therapy

Untreated/active psychiatric illness

Active cigarette smoking

Active drug or alcohol abuse/addition

Pregnancy

* “Ability to form a therapeutic alliance” refers to an ability to work cooperatively with the transplantation team throughout work-up, transplantation and follow-up.

A criterion that requires further discussion before inclusion in local protocols is a requirement that the patient have tried and failed with prosthetics. Financing of prosthetics in Australia means that access is an issue; however, there would likely be value to the potential recipient in being assessed for and trialling basic prosthetics to gain an understanding of what the sensation of the transplant will be like.

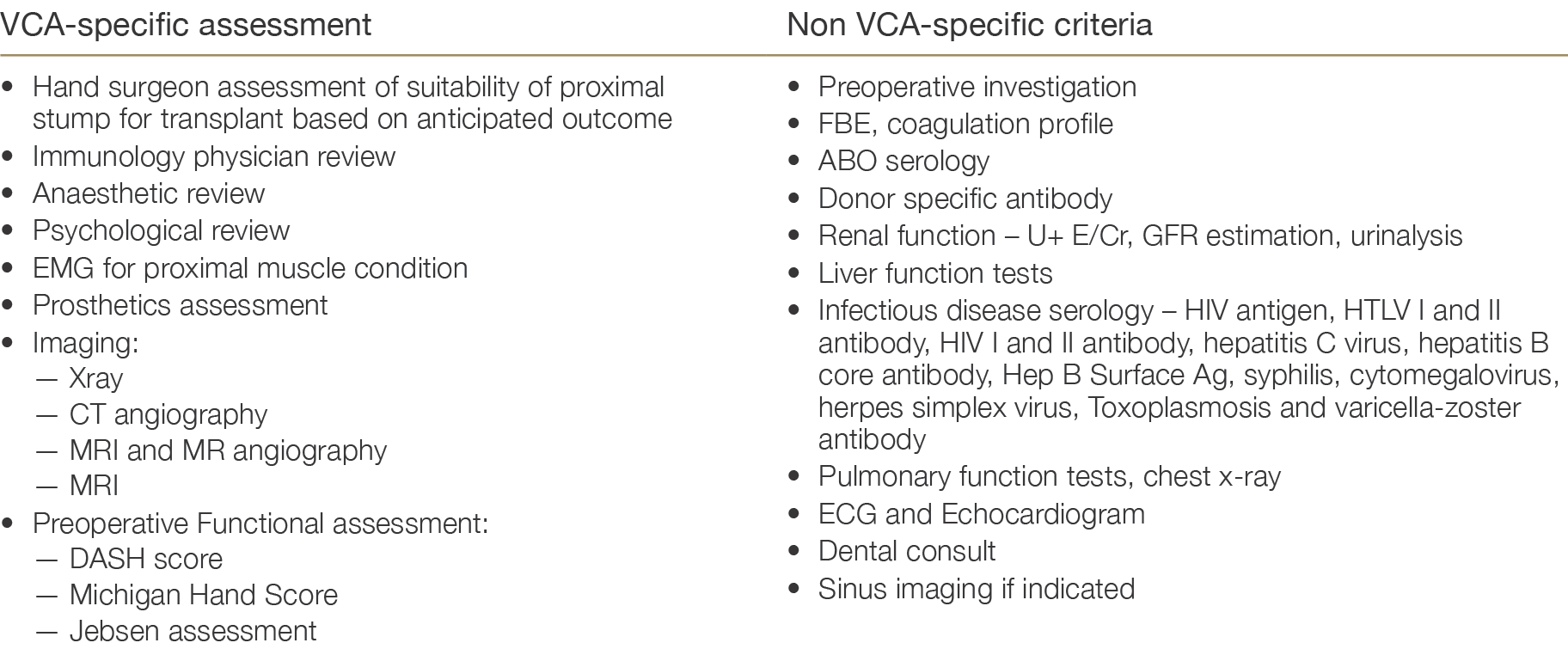

10.2.2 Assessment and acceptance

As for other solid organ transplantation, potential VCA recipient evaluation includes the major criteria of preoperative surgical suitability, infectious disease screening and malignancy screening. There are additional assessments specific to VCA and the patient assessments required in the case of hand transplantation are listed in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2: Patient assessments required prior to listing for hand transplantation

10.2.3 Retransplantation

There is currently no intention to exclude candidates on the basis of prior VCA transplant. The reasons for the loss of the prior graft would be considered as part of the psychological evaluation and assessment of ability to comply with therapy. Self-inflicted trauma is also not a contraindication to VCA transplantation: provided candidates are deemed to be currently psychologically well and stable and meet all other criteria, then they are eligible for VCA transplantation.

10.2.4 Criteria for activation on waiting list

As for other solid organ transplant procedures, the decision to activate a recipient for a VCA is based on agreement between all of the teams involved (surgical, medical and psychological). Given the ethical and health implications for the patient of a negative transplant outcome, a robust approach to risk minimisation is encouraged.

The recipient consent form developed by the St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne team includes information on the transplant operation, the potential long-term effects of transplantation, and what the recipient should expect from the transplant and the rehabilitation process. Potential recipients are informed of the following:

Hand transplant does not prolong life, instead benefits are measured in improved quality of life

Studies so far indicate that the function of the transplanted hand is better than that of prosthetics

Success of the transplant depends as much on the extensive care following the transplant as it does on the surgery itself—some of these therapies are life-long

Technical success of the surgery will be apparent in two to three days; by two to three months it is expected that the recipient will be able to make a fist, but it will be at least a year before finer finger moments and sensation to the skin develop

A hand transplant is not the best option for everyone, and risks include:

— risks related to the operation (infection, bleeding), those related to the anaesthetic and other post - operative complications which make, rarely, result in death

— rejection, which in some cases may lead to the hand needing to be surgically removed

— potential to develop certain infections, cancers, diabetes and heart disease as a consequence of immunosuppressive medicationsInclusion in the International Hand Transplant Registry (handregistry.com)

Responsibilities of the recipient include:

— Daily blood tests for the first 30 days, and weekly skin biopsies

— Medication adherence

— Hand physiotherapy

— Clinic visitsConsiderations of the donor family—in order to protect and maintain the privacy of the donor family, the recipient is requested not to share details of the transplant with the media.

It is further recommended that the consent process incorporate a cooling off period whereby, after the recipient gives their initial consent, the recipient considers their decision for approximately 4 weeks and is then asked to re-consent. This cooling-off period is an important ethical safeguard in the consent process.33 Bramstedt KA. Informed consent for facial transplantation. In M.Z. Siemionow (Ed.). The Know-How of Face Transplantation . London, UK: Springer, 2011. ×

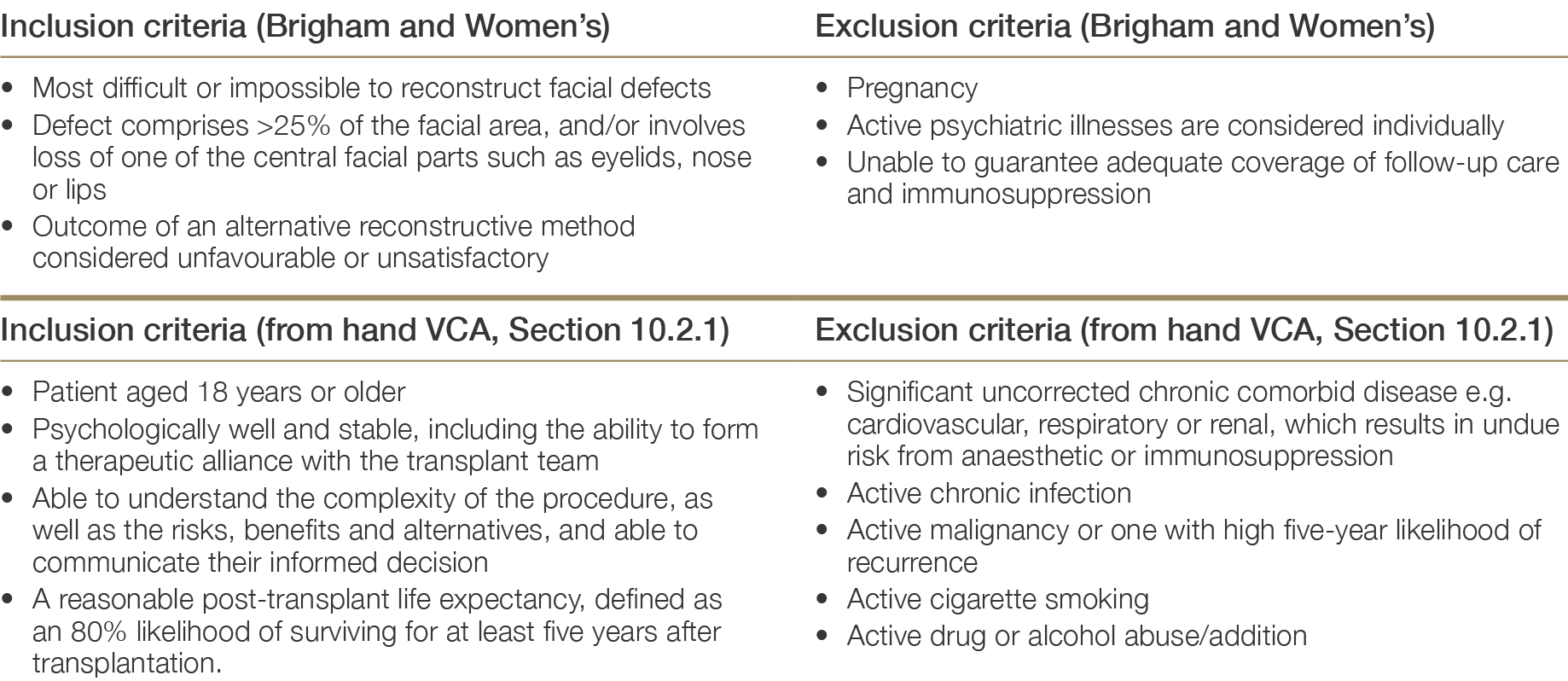

10.3 Recipient eligibility criteria: face transplantation

Though Australian recipient eligibility criteria for face transplantation have not yet been developed, other international groups have well-developed protocols. The Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston has performed multiple partial and full-face transplants since gaining institutional review board approval for the procedure in 2008. The recipient eligibility criteria specified under the protocols of this institution are listed in the Table 10.3 adapted to reflect Australian hand transplant eligibility criteria (see Section 10.2).

10.3.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 10.3: Recipient inclusion and exclusion criteria specified under Brigham and Women’s Hospital protocols for face transplantation,4 adapted for the Australian context.4 Pomahac B, Diaz-Siso JR, Bueno EM. Evolution of indications for facial transplantation. British Journal of Plastic Surgery; 2011;64(11):1410–6. ×

10.3.2 Assessment and acceptance

Similarly, Australian protocols for face transplant candidate evaluation have not been developed. The protocols for face VCA candidate evaluation used by Brigham and Women’s Hospital provide an example of the steps involved in this process.4,54 Pomahac B, Diaz-Siso JR, Bueno EM. Evolution of indications for facial transplantation. British Journal of Plastic Surgery; 2011;64(11):1410–6. 5 No reference text available.×

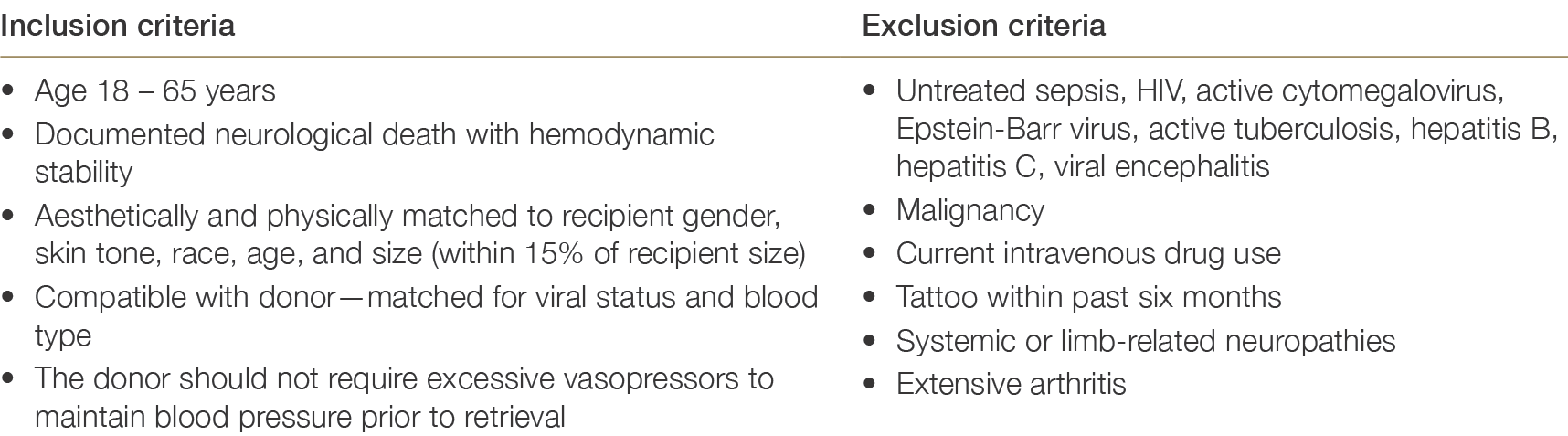

10.4 Donor Assessment

In terms of donor selection, the requirement for the donor hand or face to be a match both in terms of medical compatibility and aesthetic appearance (skin tone, proportion, age, race, gender) is unique to VCA. Secondly, because VCA is performed on physically healthy but severely disabled individuals, strict criteria are necessary to prevent donor transmission of disease. Approaching the families of potential hand and face donors also requires specialised protocols that account for the sensitivity of the request and a lower willingness to consent to donation. Protocols are also required for the fitting of prostheses to replace the donated allograft post-mortem. Further, cold ischaemia time—and therefore travel time—between retrieval and implantation must be minimal. The length of time that a potential recipient will wait for a suitable donor may therefore be extensive: this is a consideration that must be factored into recipient evaluation and informed consent.

Table 10.4 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria for hand donation that are currently applied in Australia.

Table 10.4: Inclusion and exclusion criteria for hand donation.

Australian protocols concerning eligibility for face donation have yet to be developed. The Brigham and Women’s Face VCA unit have established criteria that include factors common to hand donation, such as ABO compatibility and age, gender and skin colour match. In addition—again in keeping with hand VCA donor assessment—the presence of active sepsis, active viral infections, tuberculosis and active/recent malignancy are considered contraindications to donor acceptance. Specific to face VCA are the exclusion criteria of congenital craniofacial disorder, facial nerve palsy, a history of significant craniofacial or neck trauma and/or surgery, or a plan by the family to hold an open casket funeral.

10.5 Allocation of VCA organs

Given the low volume of VCA transplantations in Australia, and as yet there are not multiple candidates simultaneously waiting for VCA, an allocation policy has not been developed. The UNOS/OPTN protocol for VCA allocation provides benchmark against which a local policy might be developed in the future. Under the UNOS/ OPTN allocation protocol, the host OPO offers VCA organs to candidates with a compatible blood type and similar physical characteristics to the donor. The OPO will first offer VCA organs to candidates that are within the OPO’s region, and secondly to candidates that are outside of the OPO’s region according to proximity. Proximity of the donor and recipient is a relevant factor in allocation given the importance of short ischaemia time.

In addition to the absolute requirements for blood group compatibility and virtual crossmatch, proposed criteria for allocation include age difference, size (especially bones), colour and texture of the skin, and soft-tissue features.1 Other factors that may be incorporated into allocation criteria include urgency and waiting time. Given the small size of the potential donor pool, HLA matching will not be feasible.1 Rahmel A. Vascularized Composite Allografts: Procurement, Allocation, and Implementation. Curr Transplant Rep, 2014;1(3):173-182. ×

10.6 Multi-organ transplantation

There should be no impediment to undertaking a quality-of-life-improving VCA at the same time as a life-sustaining solid organ transplant. In this instance, the main ethical challenge of a VCA—that of a potential reduction in life years due to immunosuppression in an otherwise healthy recipient—are mitigated. Multiple VCA transplants (i.e. dual hand transplants) are less commonly undertaken internationally due to the challenging and prolonged recovery period for the patient, and none have yet been undertaken in Australia. For suitable candidates, however, multiple VCA would be considered.

10.7 Emerging Issues

Ethics assessment in VCA transplantation

The ethical complexity of VCA is unlike any other area of transplant medicine. Clinical ethicists are often members of VCA teams, assisting with the development of protocols, policies, procedures, and forms. The VCA clinical ethicist can also be involved in screening potential recipient for matters of ethical relevance, including but not limited to capacity assessment and informed consent, as well as coercion and conflict of interest. VCA does not save lives, but hopes to enhance them (without any guarantees), and the expectations and outcomes of the patient and surgical teams may conflict. It is important to understand these matters, as well as the motivations and motivation level of the potential recipient. The philosophical meaning attached to the hand/face/etc. by the patient must be understood, as well as the values, behaviours and emotions that are linked to these body parts. It is important to detect and resolve moral distress pertaining to the donation and transplant, including donor-related issues such as death and dying, fingerprints and identity, and personhood issues. The involvement of a clinical ethicist may therefore be a part of local VCA transplantation protocols in the future.

Psychosocial evaluation in VCA transplantation

Given that the primary goal of VCA is to improve the psychosocial status and quality of life of the recipient, psychosocial evaluation both before and after transplantation is critical not only to establish patient suitability and identify at-risk patients and those in need of ongoing counselling, but also to assess the success of the transplant itself. Psychosocial evaluation should therefore ideally establish (i) a detailed baseline understanding of the impact of the injury on the patient and the extent to which they have adapted to their disability, (ii) the existence of any demonstrable active or untreated psychiatric or psychological impairment that would preclude VCA transplantation, (iii) patient perceptions of the goals of treatment and their expectations post-transplant (also relevant to informed consent), (iii) requirements for psychosocial support pre- and post-transplantation, and (iv) post-transplant changes in quality of life and other psychosocial outcomes over the longer term. It must be further established that the potential VCA recipient will be able to tolerate the physical and psychological stress of all pre-, peri- and post-operative procedures and rehabilitation involved, while simultaneously coping with media attention, a changed physical appearance and a complex immunosuppression regimen.55 No reference text available.×

Therefore—in addition to the standard pre-transplant evaluation of psychiatric wellbeing, social support, substance use, knowledge of transplantation and predicted compliance—VCA transplantation also requires the assessment of body image, adaptation to the trauma, cognitive preparedness, motivation, expectation of transplant outcomes, and potential for psychological regression of the transplant candidate. 2 The principle concern is the potential for a recipient to psychologically reject or otherwise be unable to cope with the transplant, leading to lower quality of life and potentially to non-adherence to immunosuppression and loss of the graft.2 Kumnig M, Jowsey SG, Moreno E, et al. An overview of psychosocial assessment procedures in reconstructive hand transplantation. Transplant International, 2014;27(5):417-27. ×

In an effort to move towards standardised psychosocial assessment of candidates for hand transplantation, the Innsbruck Psychological Screening Programme for Reconstructive Transplantation (iRT-PSP) was developed in 2011. 2 This assessment method measures cognitive functioning, affective status, psychosocial adjustment, coping, quality of life and life satisfaction based on a semi-structured interview, standardised psychological screening procedures and ongoing follow-up assessment. The iRT-PSP therefore provides a tool for pre-transplant assessment, post-transplant follow-up ratings, and the identification of needs of psychological/ psychiatric treatment. The application of standardised psychosocial assessment tools will, in the future, be a part of the VCA candidate assessment process.2 Kumnig M, Jowsey SG, Moreno E, et al. An overview of psychosocial assessment procedures in reconstructive hand transplantation. Transplant International, 2014;27(5):417-27. ×