5 Kidney

Most patients with kidney failure would live longer, feel healthier, and have a better quality of life with a kidney transplant compared to staying on dialysis.1–4 The quality-of-life benefits from transplantation mean that some patients may still wish to receive a kidney transplant even if it might not increase their life expectancy.1 Port FK, Wolfe RA, Mauger EA et al (1993) Comparison of survival probabilities for dialysis patients vs cadaveric renal transplant recipients. JAMA 270(11): 1339–43. 2 Schnuelle P, Lorenz D, Trede M, et al. Impact of renal cadaveric transplantation on survival in end-stage renal failure: evidence for reduced mortality risk compared with haemodialysis during long-term follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol, 1998;9(11): 2135–41. 3 Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med, 1999;341(23):1725-30. 4 McDonald SP and Russ GR. Survival of recipients of cadaveric kidney transplants compared with those receiving dialysis treatment in Australia and New Zealand 1991–2001. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2002;17:2212–19. ×

For approximately 30 years, the Renal Transplant Advisory Committee (RTAC) and state Transplant Advisory Committees have continually developed, reviewed, and updated kidney transplantation and allocation protocols. This process takes account of changes in donor numbers and characteristics, transplant outcomes, tissue typing technology, and improved allocation practices.

In New Zealand, the National Kidney Allocation Scheme (NKAS) is managed by the National Renal Transplant Leadership Team (NRTLT). NKAS allocates deceased donor kidneys nationally, based predominantly on waiting time on dialysis and Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) matching. For details, visit: NZ Kidney Allocation Scheme December 2022 (health.govt.nz)

At the forefront of Australia’s kidney allocation protocols is the Kidney National Allocation Algorithm, (see Section 5.4.2 and Appendix C). This includes a National Allocation Algorithm and a State Allocation Algorithm. The National Allocation Algorithm is designed to facilitate the allocation of kidneys to recipients who are (i) highly sensitised (those with many HLA-antibodies) and may otherwise wait a very long time to find an immunologically compatible donor, (ii) medically urgent, or (iii) a good immunological match with the donor, especially if also young. If the donor kidneys are not both allocated via the National Algorithm the available kidney(s) will be allocated within the state in which they were donated, according to the State Allocation Algorithm.

5.1 Recipient eligibility criteria

The number of deceased donor kidneys available for transplantation is far lower than the number of patients who might benefit from a kidney transplant.5,6 In Australia, only patients who have commenced dialysis are eligible to be listed to receive a deceased donor kidney transplant (with very rare exceptions). In New Zealand, patients with progressive chronic kidney disease and an estimated GFR of less than 15 ml/min/1.73m2 who are within 6 months of requiring dialysis are eligible for inclusion on the kidney transplant waiting list (regardless of whether they have commenced dialysis). The Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA) report on the incidence, prevalence and outcomes of dialysis and transplant treatment for patients with kidney failure across Australia and New Zealand.7,8,9,10 In Australia and New Zealand, unadjusted one-year patient and graft survival rates for primary deceased donor grafts have been stable at around 98% and 96% respectively for the past ten years.5 Mathew T, Faull R, and Snelling P. The shortage of kidneys for transplantation in Australia. MJA, 2005;182(5): 204–05. 6 Veroux M, Corona D and Veroux P. Kidney transplantation: future challenges. Minerva Chirurgica, 2009;64(1): 75–100. ×7 ANZDATA Registry. 47th Annual Report, Chapter 2: Prevalence of Kidney Failure with Replacement Therapy. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, 2024. (Available from: http://www.anzdata.org.au ). 8 ANZDATA Registry. 47th Report, Chapter 1: Incidence of Kidney Failure with Replacement Therapy. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, 2024. (Available from: http://www.anzdata.org.au ). 9 ANZDATA Registry. 47th Report, Chapter 6: Australian Kidney Transplant Waiting List. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, 2024. (Available from: http://www.anzdata.org.au ). 10 ANZDATA Registry. 47th Report, Chapter 7: Kidney Transplantation. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, 2024. (Available from: http://www.anzdata.org.au ). ×

Receiving a transplant has inherent risks associated with surgery and immunosuppression that need to be weighed up against the possible benefits. Patients need to be well informed by their clinical teams and accept their own individual transplant-related risks prior to listing.

Prior to 2018, it was an Australian requirement that patients have an 80% likelihood of survival at five years post-transplant to be eligible for deceased donor kidney wait-listing. This is no longer an absolute requirement. Eligibility for deceased donor kidney transplant wait-listing in Australia now requires that potential kidney transplant candidates have a high likelihood of significant benefit from kidney transplantation. Any significant risk of death post-transplant from complications (e.g. heart disease, vascular disease, cancer, infection) or general frailty would be a contraindication to kidney transplantation. This risk-benefit assessment is a clinical decision best made by the local multidisciplinary transplant team comprising of transplant physicians, surgeons, coordinators, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers who are experienced in managing both dialysis and transplant patients.

In New Zealand, an estimated 80% likelihood of survival at five years post-transplantation remains an eligibility requirement for deceased donor kidney transplantation. While this may be difficult to determine, New Zealand units use an algorithm to estimate survival probability.11 These calculation tools are also used by other centres around the world to estimate an individual’s post-transplant survival based on various factors.1211 Lim WH, Chang S, Chadban S, et al. Donor-recipient age matching improves years of graft function in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2010;25(9):3082-9 ×12 Baskin-Bey ES, Kremers W and Nyberg SL. Improving utilization of deceased donor kidneys by matching recipient and graft survival. Transplantation, 2006;82(1):10-4. ×

5.1.1 Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for being listed for deceased donor kidney transplantation are:

Kidney failure requiring dialysis (Australia) or progressive chronic kidney disease in patients who are within 6 months of requiring dialysis and a GFR <15 ml/min/1.73m2 (New Zealand);

Low anticipated likelihood of perioperative mortality and a reasonable estimated post-transplant patient and allograft survival. Factors that may influence graft survival include primary causes of kidney failure that are likely to recur after transplantation (therefore resulting in premature graft failure), infection risk and concerns regarding non-adherence with immunosuppression.

Age: advanced age in the absence of significant medical comorbidity and cognitive or neuropsychiatric deficits is not a contraindication to kidney transplantation; however only 2% of the dialysis patients in Australia aged over 65 were on the waiting list for kidney transplantation at 31 December 2023 due to the high rates of comorbidities in this population.7,9 A number of patients over the age of 70 with limited comorbidities have been transplanted successfully.7 ANZDATA Registry. 47th Annual Report, Chapter 2: Prevalence of Kidney Failure with Replacement Therapy. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, 2024. (Available from: http://www.anzdata.org.au ). 9 ANZDATA Registry. 47th Report, Chapter 6: Australian Kidney Transplant Waiting List. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, 2024. (Available from: http://www.anzdata.org.au ). ×

5.1.2 Exclusion criteria

Criteria that are considered relative or absolute contraindications for deceased donor kidney transplantation wait-listing include:

Australia: if the perioperative and post-transplant risks outweigh the likelihood of deriving significant benefit from transplantation; New Zealand: if there is a lower than 80% likelihood of surviving at least five years following transplantation.

Comorbidities that might have a significant impact on the life expectancy of a kidney transplant recipient include cardiac disease, vascular disease, infection risk and malignancies.13–1813 Medin C, Elinder CG, Hylander B, et al. Survival of patients who have been on a waiting list for renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2000;15(5): 701–04. 14 Wheeler DC and Steiger J. Evolution and etiology of cardiovascular diseases in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation, 2000;70(Supp):SS41. 15 Pascual M, Theruvath T, Kawai T, et al. Strategies to improve long-term outcomes after renal transplantation. N Engl J Med, 2002;346: 580–90. 16 ANZDATA Registry. 45th Report. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2022. (Available from: http://www.anzdata.org.au ). 17 Penn I. The effect of immunosuppression on pre-existing cancers. Transplantation, 1993;55(4):742. 18 Kasiske BL, Ramos EL, Gaston RS, et al. The evaluation of renal transplant candidates: clinical practice guidelines. Patient Care and Education Committee of the American Society of Transplant Physicians. J Am Soc Nephrol, 1995;6(1):1. ×

Cardiovascular disease: severe, non-correctable cardiovascular disease is an absolute exclusion criteria. Lesser degrees of disease would also potentially contribute to a lower anticipated post-transplant survival, and hence would be considered a relative contraindication.19,2019 Mistry BM, Bastani B, Solomon H, et al. Prognostic value of dipyridamole thallium-201 screening to minimize perioperative cardiac complications in diabetics undergoing kidney or kidney-pancreas transplantation. Clin Transplant,1998;12:130–35. 20 De Lima JJ, Sabbaga E, Vieira ML, et al. Coronary angiography is the best predictor of events in renal transplant candidates compared with noninvasive testing. Hypertension, 2003;42:263–68. ×

Diabetes mellitus: uncomplicated diabetes mellitus is not a contraindication to transplantation. Patients with diabetes should undergo a detailed assessment for any vascular complications that may affect their anticipated post-transplant survival; such vascular complications would be a relative consideration.21,2221 Cecka JM. The UNOS Scientific Renal Transplant Registry. Clinical Transplants, 1996:1-14. 22 Fernandez-Fresnedo G, Zubimendi JA, Cotorruelo JG, et al. Significance of age in the survival of diabetic patients after kidney transplantation. Int Urol & Nephrol, 2002;33(1):173–77. ×

Infection: uncontrolled infection is a contraindication to transplantation. Patients may be listed and transplanted once the infection has been adequately treated.

Malignancy: active malignancy is generally considered a contraindication to kidney transplantation (see Table 2.7). However, patients with a history of malignancy deemed to be cured may be suitable for transplantation. The decision whether to refer a patient with a history of malignancy for kidney transplant assessment needs to be made on a case-by-case basis, and generally should only be made in consultation with an oncologist or other appropriate specialist.

Non-adherence to complex medical management: the ability to correctly follow a treatment plan— particularly with respect to anti-rejection medications—is an important factor in successful outcomes following kidney transplantation and, as such, is a requirement for listing. Likelihood of adherence is assessed by the transplanting units social and psychiatry team; every effort should be made to assist patients and their carers to optimise adherence to therapy.

Other medical conditions: patients with kidney failure can have any number of comorbid medical conditions that may affect the risk of complications and survival after transplantation. These include but are not limited to, cardiac disease, chronic lung disease, cirrhosis of the liver, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease. Whether the existence of any such conditions is an absolute or relative contraindication to kidney transplantation needs to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Surgical exclusions including complex vascular anatomy and heightened risks associated with significant obesity.

5.1.3 Assessment and acceptance

Patients referred for kidney transplantation (from kidney/dialysis units) should be initially assessed by the transplanting hospital team, with regular review of patients after listing to ensure ongoing medical, psychological and surgical suitability. Initial and subsequent patient assessments and decisions regarding acceptance onto the waiting list in OrganMatch and continued eligibility for listing should involve a transplant nurse, physician and surgeon. The Director of a transplant unit (or their delegate which may include transplant clinicians and transplant coordinators) has the authority to add or remove patients from the kidney transplant waiting list.

5.1.4 Retransplantation

Patients who are being considered for a second or subsequent kidney transplant should be assessed according to the same criteria as candidates who are being assessed for their first kidney transplant. The vast majority of kidney transplant procedures are performed in first-time recipients. In Australia and New Zealand over the past decade, approximately 10% of recipients have received two or more kidney transplants. Only 1–2% of recipients receive a third or subsequent kidney transplant.

5.2 Waiting list management

The waiting list is comprised of patients who have been assessed by a transplant physician and surgeon and determined to be suitable to undergo kidney transplantation. Where possible, this assessment process should commence prior to initiation of dialysis. The total time from referral for transplant assessment to activation on the TWL can vary considerably depending on each individual’s underlying medical and surgical concerns, the investigations required, the need for opinions from other specialists and many other factors. For referred patients who are relatively healthy with few comorbidities, activation on the TWL should ideally occur within the first 6 months of commencing dialysis.

Patients must be enrolled in the Kidney TWL program in OrganMatch in order to be matched with deceased organ donors. It is not a chronological list: organs are offered to waitlisted candidates according to the national and state allocation protocols (see Sections 5.4 and 5.5) which take into account recipient sensitisation, donor-recipient HLA-match and waiting time. There are certain circumstances in which a patient may be given priority (e.g., patients under 18 years of age; see Section 5.2.4). Once a patient is accepted onto the TWL and enrolled in OrganMatch, blood samples should then be sent to the state tissue-typing laboratory. The status of TWL candidates is made “ready” when tissue- typing and HLA antibody (luminex) screening (Section 5.2.6) is complete. Once a patient’s status is “ready” in OrganMatch the patient can be matched with deceased organ donors.

To maintain an accurate HLA profile for each waitlisted patient, monthly tissue typing bloods are required and sensitisation events such as blood transfusions, vaccinations, infections, should be monitored closely and reported back to state tissue-typing laboratories. Further details on sensitisation history can be found in section 5.2.6.1

When patients develop a lot of antibodies against other peoples’ tissue type (HLA-antibodies) – sensitisation—it can be very difficult to find a suitable kidney for them (i.e., one that they do not have antibodies against). These patients require preferential access to a well-immunologically matched kidney if one becomes available. The ability to measure a patient’s level of sensitisation has improved, along with an enhanced allocation algorithm that can provide priority matching to best meet the needs of these sensitised patients.

5.2.1 Calculation of waiting time

In Australia, waiting time is calculated from the date that long-term dialysis was commenced (not from the date of acceptance onto the waiting list). This is because delays in active listing may arise due to medical issues or delays in completing the necessary investigations that are outside the control of the patient. It is critical that all patients are adequately tested and prepared for transplantation, and therefore it is important for work-up investigations to be completed thoroughly. When calculating waiting time, periods of acute or temporary dialysis prior to the date that long-term dialysis was commenced do not contribute to waiting time.

In New Zealand, waiting time is calculated as the number of months from the date of chronic dialysis initiation for treatment of end stage renal failure (or recommencement after a failed kidney transplant) to the date of offer of a kidney. Where patients recover independent renal function unexpectedly after chronic dialysis initiation for the treatment of end stage renal failure, waiting time shall be calculated from the date of subsequent initiation of chronic dialysis for treatment of end stage renal failure.

For a second or subsequent transplant, waiting time is calculated from the date that dialysis was recommenced (Australia and New Zealand), following failure of the previous transplant. Sometimes, a kidney transplant will fail very early or never function at all. When a deceased donor kidney transplant fails very early, as a result of technical issues or the poor quality of the donor kidney, it may be possible for the patient to retain their original waiting time credit (This would not apply in the case of graft loss due to non-adherence to treatment).

In Australia, if a kidney transplant fails within the first 12 months, the recipient is able to retain their original accrued waiting time credit when/if they are re-listed for a subsequent transplant. This makes allowance for kidney transplants that are performed but never functioned very well or had technical issues. Approval for reinstatement of waiting time in these circumstances needs to be obtained from the relevant state-based renal transplant advisory committee.

Live donor kidney recipients in whom the graft fails within the first 12 months post-transplant may be able to retain their previously accrued waiting time, if approved by the relevant state or national transplant advisory committees. This removes the risk of the possible loss of accrued waiting time as a disincentive to proceed with a live donor. The number of live donor kidney transplants that are lost in the first year are very low.

In New Zealand, if a patient meets renal failure criteria for listing within one year after kidney transplantation, the recipient will be reinstated on the waiting list with the same waiting start date they had prior to the most recent transplant if they otherwise are or subsequently become eligible for deceased donor listing.

5.2.2 Ongoing review

To remain active on the TWL, patients must continue to be medically, psychologically and surgically suitable to receive a kidney transplant, and should undergo regular reassessment by the transplant unit. Reassessment of patients on the TWL should occur at least annually; usually this would be a face-to-face assessment. It is expected that to remain on the TWL a patient should continue to fulfil the same inclusion criteria as at their initial listing. Transplant units should have a process to formally ensure that ongoing patient reassessment occurs and that actively listed patients are suitable to receive a kidney transplant.

Sometimes an event occurs requiring a patient’s enrolment status to be changed to “on hold”. On hold status is temporary. If a patient is no longer suitable for transplant, the enrolment must be ended in OrganMatch. For example, the development of un-correctable substantial cardiac disease would mean that a waitlisted person is no longer suitable and so their enrolment in OrganMatch would be ended. If, however, a patient had a treatable infection, such as peritonitis, their status would simply change to “on hold” until the infection resolved, provided no other changes occur that affect eligibility. Patients should be kept informed of their status on the TWL.

5.2.3 Urgent patients

In rare circumstances (applicable in Australia but not in New Zealand) a patient who is active on the transplant waiting list may be deemed ‘urgent’; for example, if they have very limited or failing dialysis access without which their survival is threatened. The decision to give a patient urgent status is state-based and is reviewed by each state’s transplant advisory committee. It is expected that—unless there is a compelling reason—the first suitable kidney offer should be accepted for patients deemed as urgent. In OrganMatch a patient needs to be flagged with a state urgency index.

5.2.4 Paediatric priority

Paediatric kidney failure patients are few in number (approximately <2% of the prevalent kidney failure population in Australian and New Zealand), and have special needs with respect to physical and psychological development that are best met by transplantation.23,24 In Australia, patients who are under the age of 18 years and have commenced dialysis are eligible for paediatric prioritisation under the National and State-based allocation algorithms. Bonus points are awarded for paediatric priority taper to zero by age 25 years.23 Dharnidharka VR, Fiorina P, Harmon WE. Kidney transplantation in children. N Engl J Med. 2014 Aug 7;371(6):549-58. 24 Motoyama O, Kawamura T, Aikawa A, et al. Head circumference and development in young children after renal transplantation. Pediatr Int, 2009;51(1):71–74. ×

Given this extra priority, paediatric recipients can expect to receive offers of kidneys that vary with respect to kidney quality and the degree of HLA matching. Transplant units need to weigh up the implications of these offers with respect to immunological considerations and projected graft longevity. In some paediatric units, both immunological exclusions (eplet based) and quality-based exclusions (e.g. setting an upper limit for donor age or donor co-morbidity) are being set for individual patients, and this approach is strongly advised. This will tend to increase the waiting time in favour of a kidney with a better immunological match and prognosis match.

In New Zealand, patients under the age of 15 at the time of allocation receive paediatric prioritisation.

5.2.5 Australian and New Zealand Paired Kidney Exchange (ANZKX) Priority

If the intended recipient of a kidney from a living donor matched through the Australian and New Zealand Paired Kidney Exchange (ANZKX)25 is unable to receive that kidney but their co-registered living donor has already donated, the “orphan recipient” will be eligible for priority listing from the national deceased donor organ pool in their country of residence.25 Australian and New Zealand Paired Kidney Exchange Program Protocol 1: ANZKX Protocol. Australian Government Organ and Tissue Authority, 2022. (Available from: https://www.donatelife.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-04/ANZKX%20Protocol%201.%20 ANZKX%20Protocol%20-%20Ver%204_Apr%202022.pdf ). ×

If the orphaned recipient is in Australia and pre-emptive (i.e. has not yet started dialysis) then an exception will be made so that these patients can be prioritised to receive a kidney from the deceased donor pool once approved by RTAC.25 In OrganMatch, these patients are listed with National Urgency status.25 Australian and New Zealand Paired Kidney Exchange Program Protocol 1: ANZKX Protocol. Australian Government Organ and Tissue Authority, 2022. (Available from: https://www.donatelife.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-04/ANZKX%20Protocol%201.%20 ANZKX%20Protocol%20-%20Ver%204_Apr%202022.pdf ). ×

If an ANZKX kidney is transplanted and kidney reperfusion has been established, the recipient will not be considered an orphan recipient, even if the kidney never functioned. However, if the transplant surgeon finds that the kidney is visibly damaged prior to surgery and proceeds but early graft loss occurs, the recipient would still be eligible to be prioritised according to the Orphaned Recipient protocol if approved by RTAC. In this situation the transplant surgeon needs to have informed the ANZKX Coordination Centre prior to proceeding with surgery.

If the orphaned recipient is in New Zealand, prioritisation for a deceased donor kidney will be discussed and approved by the New Zealand NRLT.

This ability to prioritise ANZKX recipients in case of unforeseen circumstances safeguards the live donors and recipients participating in the ANZKX program. Since 2021, ANZKX has moved to continuous matching and no longer performs match runs. By performing continuous matching, the program aims to reduce the waiting time from match offer to transplant to approximately 60 days or less. Historically, with match runs the average waiting time was around 100 days.

5.2.6 Histocompatibility Assessment

Prior to waitlisting, each transplant candidate must undergo a series of tests performed at the state Tissue Typing laboratories. These include:

HLA typing using the molecular technique Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) at the following HLA loci: A, B, C, DRB1, DQB1, DQA1, DPB1, DPA1. If present, DRB3, DRB4, DRB5 should also be included.

HLA antibody screening using Luminex single antigen technology to detect the antibodies to HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, -DRB3, -DRB4, -DRB5, -DQA1, -DQB1, -DPA1, and -DPB1. This screening must have occurred within 120 days to be included in matching. It is optimal for all waitlisted patients to be screened every 3 months.

5.2.6.1 Defining Unacceptable Antigens

On completion of patients’ HLA typing and HLA antibody screening results, the histocompatibility laboratory provides an evaluation of histocompatibility data and recipient immunologic risk that will allow the clinical unit to decide on appropriate induction and immunosuppression approaches to transplantation. The assessment should provide an individualised list of HLA antigens that would be unacceptable in a donor and should consider:

The recipient’s sensitisation history

a. Previous transfusion of blood products

b. Numbers of pregnancies and age of youngest child

c. Repeat mismatches from previous transplantsDetection and characterisation of HLA-specific antibodies

a. The strength of the various HLA-specific antibodies

b. Stability of antibody strength over time - decreasing or increasingLikelihood of repeat transplant in the future

a. Consider avoidance of potential donor HLA mismatches with high eplet loads.

All HLA antigens to be avoided in potential donors will be defined unacceptable antigens and listed in the following categories:

Antibody sourced (antigens to which there is evidence of historical or current HLA antibodies)

Previous donor mismatches

Other antigens for exclusion (e.g., potential high eplet load mismatches)

Once defined, the unacceptable antigens are used in the TWL matching algorithms to exclude potential recipients from incompatible organ offers. Waitlisted patient’s HLA antibodies must be performed every 120 days – if this is not done the patient will not be matched with deceased organ donors. The waitlisted patients’ assigned unacceptable antigens are also assessed and reviewed after every antibody screen. Additional comprehensive information is available within the National Histocompatibility Guidelines: https://tsanz.com.au/ storage/Guidelines/TSANZ_NationalHistocompatibilityAssessmentGuidelineForSolidOrganTransplantation_04.pdf

5.3 Donor assessment

Various medical factors have been found to influence long term kidney graft function, in particular donor age and history of diabetes, hypertension or vascular disease.26,27 Internationally, transplant centres are increasingly using donor characteristics in allocation decisions in an effort to optimise the transplant outcomes from each donated kidney.28,29 In 2021, implementation of a revised kidney matching algorithm included, in part, KDPI-EPTS matching (prognosis matching) to improve organ utilisation. This is described in more detail in Section 5.426 Collins MG, Chang SH, Russ GR and McDonald SP. Outcomes of transplantation using kidneys from donors meeting expanded criteria in Australia and New Zealand, 1991 to 2005. Transplantation, 2009;87(8):1201-9. 27 Pascual J, Zamora J and Pirsch JD. A systematic review of kidney transplantation from expanded criteria donors. Am J Kidney Disease, 2008;52(3):553-86. ×28 Israni AK, Salkowski N, Gustafson S, et al. New National Allocation Policy for Deceased Donor Kidneys in the United States and Possible Effect on Patient Outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2014;25:1842-1848. 29 Eurotransplant Manual. Chapter 4: Kidney (ETKAS and ESP). Eurotransplant, Leiden, 2023. (available from: https://www. eurotransplant.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/H4-Kidney-2023.1-January-2023.pdf ). ×

5.3.1 Donor information and testing

As described in Chapter 2, all deceased donors undergo a detailed general assessment of medical suitability, which includes kidney function assessment through the patient’s past and current medical history and medical investigations. In some cases, a kidney biopsy of the donor kidney is performed, which can be useful particularly in the case of donors with significant cormorbidities.3030 Remuzzi G, Cravedi P, Perna A, et al. Long-term outcome of renal transplantation from older donors. N Engl J Med, 2006;354(4):343-352. ×

Given an increasing number of older donors, often with significant cardiovascular disease, some donated kidneys are thought to not be able to provide adequate function after transplantation. In a proportion of these cases, both of the kidneys from the one adult donor are offered to a single recipient (dual). This is to ensure that at least one patient can be transplanted with a successful outcome.3030 Remuzzi G, Cravedi P, Perna A, et al. Long-term outcome of renal transplantation from older donors. N Engl J Med, 2006;354(4):343-352. ×

For information on kidney donation from paediatric donors, see Chapter 11.

5.3.2 Donor-related risk

The quality of kidneys retrieved from deceased donors can vary significantly. Donor age may be anywhere from 3 months to 85 years. In 2023, the mean age of deceased donors was 47 years in Australia and 43 years in New Zealand.31 Donors aged over 65 years accounted for 15% and 11% of all deceased donors in Australia and New Zealand respectively.31 Kidney function can also vary depending on the existence of any underlying disease processes in the donor (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, or vascular disease). Studies support the utility of transplanting kidneys from donors who are older or have diabetes, hypertension, or vascular disease, as this increases the total number of kidneys available and gives more people the opportunity to be transplanted. Whilst recipients benefit from transplantation over remaining on dialysis, long-term recipient outcomes with these kidneys are poorer.26,2731 ANZOD Registry. 2024 Annual Report, Section 4: Deceased Organ Donor Profile. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2024. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au ×31 ANZOD Registry. 2024 Annual Report, Section 4: Deceased Organ Donor Profile. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2024. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au ×26 Collins MG, Chang SH, Russ GR and McDonald SP. Outcomes of transplantation using kidneys from donors meeting expanded criteria in Australia and New Zealand, 1991 to 2005. Transplantation, 2009;87(8):1201-9. 27 Pascual J, Zamora J and Pirsch JD. A systematic review of kidney transplantation from expanded criteria donors. Am J Kidney Disease, 2008;52(3):553-86. ×

The concept of a “Kidney Donor Risk Index” (or KDRI) has been developed in order to rank the quality of each donor kidney.32 The KDRI is converted to a Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) by remapping onto a percentage scale. Kidneys with a low KDPI are expected to have longer post-transplant survival than those at the other end of the spectrum. Factors included in the calculation of this index are donor age, donor kidney function, presence of diabetes or hypertension, cause of death, and donation pathway (neurological death or circulatory determination of death).32 Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, et al. A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: the kidney donor risk index. Transplantation, 2009;88(2):231–6. ×

Within OrganMatch it is now possible for a patient with their nephrologist to indicate a specific maximum level of KDPI (KDPI max) that they are willing to accept.

It is important to note that, in estimating kidney quality, it is not possible to account for all potential donor-related risk factors and there is always the possibility that some unknown factor may affect the transplant outcome. All transplantation procedures carry some risk and recipients should be made aware of these general risks before being listed for transplantation. Units are expected to have a thorough patient education process that discusses these issues in detail prior to patients being listed and then transplanted. Some states use a consent form that is discussed with the patient and signed prior to listing, in order to communicate the various risks and expectations of the transplant process.

In some cases, there may be important additional factors that need to be discussed with the recipient before they consent to proceed with a specific transplant. This is important if there appears to be some additional risk related to the donor, or if other factors have been identified that may influence the transplant outcome. Examples include:

The likelihood the kidney will have delayed function requiring dialysis for a period of time after the transplant surgery—approximately one-third of kidneys transplanted do not function immediately

The possibility that the kidney will have poor function

The risk of infection or cancer transmission if there are factors in the donor history that increase their risk, even though screening tests may be negative

Anatomical problems that may have been identified in the donor kidney

Greater than usual immunological barriers between the donor and recipient, such as the identification of donor-specific HLA-antibodies in the recipient—these may lead to an increased risk of rejection and/or the need for additional treatment such as plasma exchange.

5.4 Allocation: Australia

Kidney allocation processes are based on certain principles (see Section 5.4.1), which have been refined over time and are under frequent review to ensure that allocation outcomes remain consistent with these stated principles. Allocation algorithms (see Sections 5.4.2 and 5.4.3) refer to the practical application of these principles and are dynamic because they need to respond to changes in medical knowledge and to shifts in donor and recipient characteristics over the longer term. To ensure that kidneys are not wasted, allocation algorithms also need to be sufficiently flexible to accommodate changes in the medical status of recipients and/or donors that necessitate deviation from the usual allocation pathway.

Similar to many practices in medicine, there may be instances where the allocation process cannot always be rigidly applied, and clinical discretion may sometimes be necessary to overcome unexpected impediments to normal allocation (see Section 5.4.5). In these rare circumstances, all cases that deviate from normal allocation practice are audited by experienced transplant clinicians through RTAC and the respective state transplant advisory committees to ensure that the deviation was acceptable and justified. Where deviations occur, the over-riding principle remains to ensure that all kidneys that can be used are effectively and fairly allocated to a wait-listed patient. In addition to unplanned allocation deviations, certain authorised deviations from usual allocation rules are also recognised. These may occur in the case of urgent listings, the Australian and New Zealand Paired Kidney Exchange Program or donors with a rare blood type (see Section 5.4.4).

To ensure the best use of kidneys from deceased donors, it is important to try to maximise the benefit to the whole community from this scarce and valuable resource.11,12 In several international programs, donor kidneys with greater estimated survival are preferentially allocated to recipients predicted to have a longer life-expectancy after transplantation; donor kidneys with shorter estimated survival are preferentially allocated to recipients predicted to have a shorter life expectancy. Acceptance of a kidney with shorter estimated survival is often with the expectation of a shorter waiting time.11 Lim WH, Chang S, Chadban S, et al. Donor-recipient age matching improves years of graft function in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2010;25(9):3082-9 12 Baskin-Bey ES, Kremers W and Nyberg SL. Improving utilization of deceased donor kidneys by matching recipient and graft survival. Transplantation, 2006;82(1):10-4. ×

Matching the quality of the donor kidney to the likely longer-term survival of the recipient is now seen as an important principle in allocation policy (as described in Section 5.3.2).11,33,34 In basic terms, kidneys with a longer predicted life span are best allocated to recipients with a longer predicted life expectancy and vice versa. This is referred to as prognosis matching. Prognosis matching aims to optimise graft survival outcomes from the available donor pool, while giving a wide range of people on dialysis the opportunity to benefit from transplantation. As of May 2021, the principle of prognosis matching was introduced into kidney matching algorithms in Australia. The Kidney Allocation Algorithm continues to be enhanced and further work is underway to improve outcomes for patients and the community.11 Lim WH, Chang S, Chadban S, et al. Donor-recipient age matching improves years of graft function in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2010;25(9):3082-9 33 Stratta RJ, Rohr MS, Sundberg AK, et al. Intermediate-term outcomes with expanded criteria deceased donors in kidney transplantation: a spectrum or specter of quality? Annals of Surgery, 2006; 243(5):594-601. 34 Merion RM, Ashby VB, Wolfe RA, et al. Deceased-donor characteristics and the survival benefit of kidney transplantation. JAMA, 2005;294(21):2726-33. ×

The ongoing development of the Australian Kidney Allocation Algorithm has also enabled greater HLA matching for younger, healthier patients who are likely to require re-transplantation in their lifetime. Kidney transplantation is one way that patients become sensitised against future transplants and this can limit the patient’s ability to find a suitable second (or subsequent) kidney if they require retransplantation in the future. Younger, healthier patients are most likely to need a second or subsequent transplant because in many cases they outlive their original graft.

Better immunological matching may improve their chances of successful retransplant in the future. Changes to the Kidney Allocation Algorithm in 2021 made a first step in this direction, by initially preferentially allocating well-matched donor kidneys to waitlisted candidates with longer estimated post-transplant survival.

5.4.1 Principles

The principle intention of the Australian Kidney Allocation Algorithm is to ensure all deceased donor kidneys are allocated to a recipient by a process that is transparent, equitable and standardised. Currently this is done according to the following criteria:

Blood group compatible (e.g., A to A) and blood group acceptable (e.g., O to B) See Appendix C for ABO selection rules

Waiting time (see Section 5.2.1)

HLA matching (tissue typing to determine the level of immunological compatibility between a donor and recipient)

HLA-antibody detection (which can identify unacceptable HLA antigens, and be used to preclude certain donors)

Certain priority allocations (e.g., paediatric recipients defined as age <18 years, combined organ recipients such as kidney-pancreas, highly sensitised recipients)

The requirement to maintain an equitable flow of kidneys between states and territories

Usually, the higher ranked recipient will be offered the left kidney, unless it is significantly smaller, poorly perfused, damaged or has challenging complex vascular anatomy, in which case it will be allocated to the lower ranked recipient.

5.4.2 Australian Allocation Algorithms

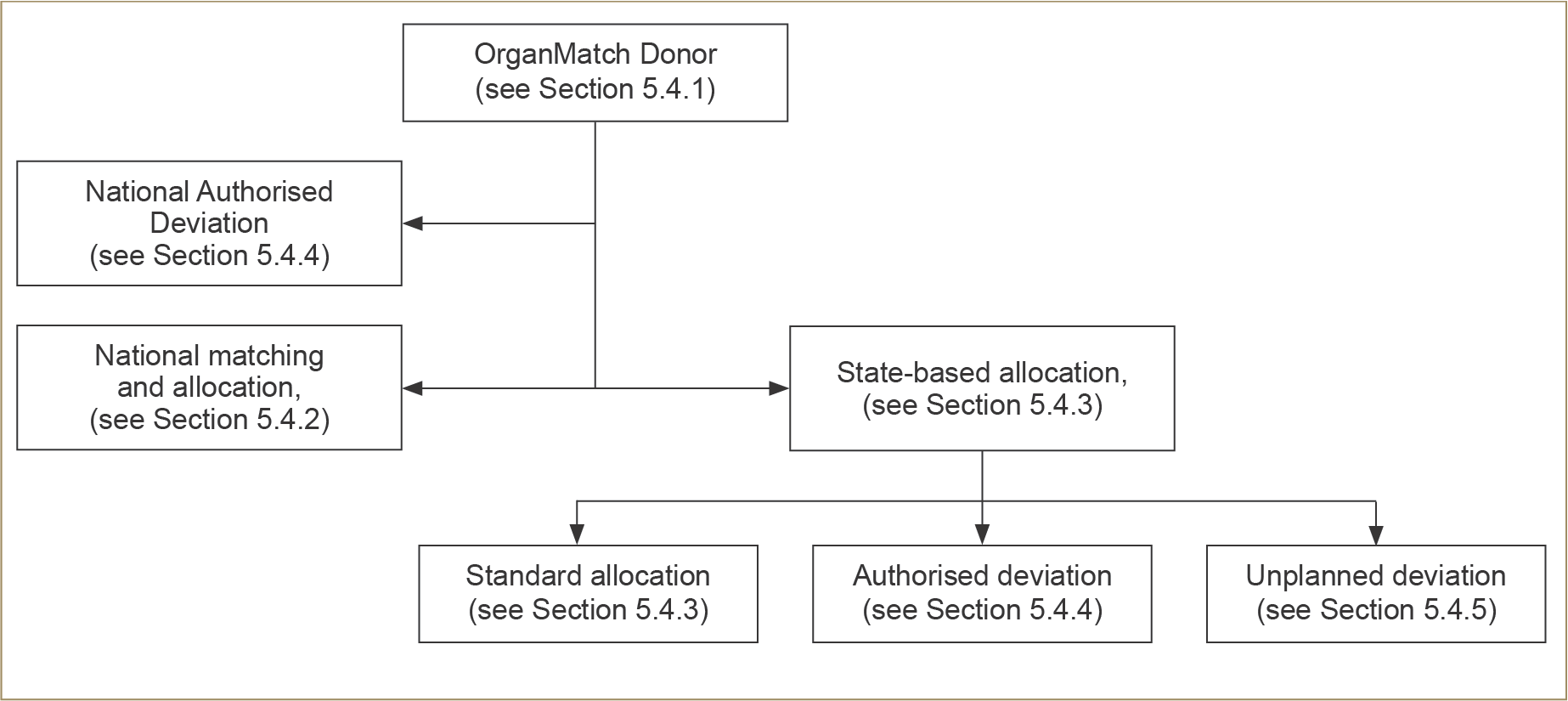

An overview of the Australian allocation process is shown in Figure 5.1 below. The specific algorithms for national and state-based allocation are transparent and available to all potential recipients (see Appendix C).

The first step of the allocation process is HLA typing of the donor to establish whether there is a recipient in any Australian state or territory who would receive a particular advantage or benefit from a specific kidney, based on a combination of their HLA-matching and unacceptable antigens. For these reasons, a proportion of kidneys are allocated based on immunological match according to the national allocation algorithm. In these situations, the kidney(s) may therefore be transported interstate. If not matched at the national level, the kidney(s) will be allocated according to the state algorithm.

The national and state kidney allocation algorithms are complex and are continuously monitored and reviewed. Previously, on average, about 20% of deceased donor kidneys are transported interstate through national allocation. The remaining 80% of kidneys remain in their donor state and are allocated according to state algorithms. However, since the updated algorithm was implemented in May 2021, giving increased priority to the very highly sensitised waitlisted candidates, there has been an increase in the proportion of kidneys being allocated via the national algorithm.

For younger recipients who have longer life expectancies and thus may need more than one transplant in their lifetime, a good immunological match) is considered more important than it is in older recipients, as a better match may minimise the formation of HLA antibodies that may lead to difficulties in finding a compatible donor in the future. For older patients and those with multiple co-morbidities, the longer-term benefit of good immunological matching is less crucial as there is a lower likelihood of requiring a subsequent transplant.

5.4.3 State-based allocation using the state allocation algorithms

The state algorithms are primarily based on waiting time and immunological matching, although to lesser degree than the national algorithm (Appendix C). It is important to note that the majority of recipients overall do not receive highly immunologically matched kidney as this is usually not possible. However, excellent graft and patient outcomes are still achieved.

Figure 5.1: Flow diagram representing an overview of the pathway by which kidney allocation proceeds after initial matching within OrganMatch.

From a practical viewpoint, state-based allocation helps to minimise cold ischaemic time and allows for a more efficient use of local donation, laboratory, and retrieval team resources. There is good evidence that shorter ischaemic times improve transplant outcomes, especially for kidneys of lower quality. An additional advantage of state-based allocation is that it allows for state-based transplant advisory committees to continually review and improve the local allocation algorithm in order to reduce inequities and imbalances within their state. It also allows states to streamline their processes for allocating kidneys that are of lower quality or pose certain additional risks (e.g., possible infection or malignancy or anatomical difficulties). These kidneys are often very difficult to successfully allocate, and efficient local systems help to achieve the best use of these organs. The state transplant advisory committees review, audit and guide the principles applied in achieving successful allocation in these less typical cases that assist in maximising organ utilisation rates.14,35 Some of these state-based scenarios are described below in Section 5.4.4 (dual organ allocation) and Section 5.4.5 (unplanned deviation).14 Wheeler DC and Steiger J. Evolution and etiology of cardiovascular diseases in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation, 2000;70(Supp):SS41. 35 Meier-Kriesche HU and Kaplan B. Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: a paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation, 2002;74(10):1377–81. ×

5.4.4 Authorised deviations in allocation

Kidney allocation algorithms allow for certain exceptions or authorised allocation deviations using the rules defined below.

Simultaneous pancreas and kidney (SPK) transplantation: SPK offers the best clinical outcomes for certain patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and kidney failure.36 When a suitable pancreas is donated for SPK transplant, one of the donor kidneys is also allocated to the same recipient. The second kidney is then available to be allocated to a kidney-alone recipient. If, however, there are two highly-sensitised (and hence more difficult to match) kidney-alone recipients who have a very good immunological match (Level 1 or 2 National Matching Score—see Appendix C) the allocation to the SPK patient will not occur (i.e., it will be vetoed) and the kidneys will be allocated to the two kidney-alone patients.36 Morris MC, Santella RN, Aaronson ML, et al. Pancreas transplantation. S D J Med, 2004;57(7): 269–72. ×

Children (paediatric recipients <18 years): because of the special needs of children with kidney failure, mechanisms for priority allocation exist for paediatric recipients in each jurisdiction to promote timely transplantation. Details of state-specific policies are provided in Appendix C.

Increased Viral Risk Donor (IVRD): donors with recent increased infectious risk behaviours (defined in Section 2.3.1) proceeding to donation within the eclipse periods for detection of HIV, HBV and HCV by nucleic acid testing (NAT) (see Table 2.3) may be allocated to well informed and consenting recipients. Recipients that consent to transplantation from an increased viral risk donor accept the small but increased risk, compared to standard-risk donors, that HIV, HBV and HCV transmission may occur, due to undetectable levels of virus at the time of testing and/or false-negative results.

Dual organ allocation (two kidneys to one recipient): occasionally, a deceased donor may have kidneys that are considered unsuitable to be used individually but still thought to provide benefit to a single individual recipient when transplanted together. In adult donors, ‘dual’ allocation may occur when the donor is elderly and has significant comorbidities which impact kidney function for example. This may also occur with the use of very small paediatric donors who are <20kg (1 to 5 year-old), or on rare instances there may be an allocation of a donor <10kg (3 to 12 month-old) to dedicated specialist centers, with relevant expertise to accept and implant infant en bloc kidneys into an adult recipient (for details see Chapter 11). The decision to offer both kidneys to one individual is made by the retrieving surgical and medical team after consultation and review of the donor and potential recipient’s characteristics. The recipient is fully informed of the risks and benefits of dual allocation.

Multiple organ transplantation (other than SPK transplantation): In some carefully selected patients, a combination of a kidney and another solid organ (usually a heart or liver) is requested in order to achieve a satisfactory patient outcome. Requests for multiple organ retrieval are made via each state’s transplant advisory committee. The organs in these cases are usually allocated within the donor state (see also Section 5.6).

Exceptional circumstances arising in the Australian and New Zealand Paired Kidney Exchange (ANZKX) Program:

There are two potential situations in which authorised allocation deviations may occur in relation to donors and recipients participating in the ANZKX:

Orphaned kidney—this is a situation where a kidney removed from a living donor participating in a kidney exchange cannot be transplanted into the matched recipient because of a problem such as the recipient has an acute deterioration at the time of anaesthetic. Under these circumstances, the “orphaned kidney” may be reallocated to a patient on the deceased donor list in the country that the kidney is located in at the point it is orphaned. Kidneys in transit between countries will be allocated in the country of arrival. Under some circumstances, input from RTAC/ANZKX Clinical Oversight Subcommittee (RACOS) might be sought if required. In Australia, the allocation of the kidney will take into account the current location of the kidney, whether there are any potential recipients at Level 1-3 on the National Allocation formula and the logistics of transporting the kidney, as described in the ANZKX National Protocol. In New Zealand, the kidney will be allocated according to New Zealand’s NKAS.3737 The New Zealand Kidney Allocation Scheme, National Renal Transplant Leadership Team, December 2022. (Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/about-ministry/leadership-ministry/expert-groups/national-renal-transplant-service/nrts-papers-and-reports#natioanl_kidney_allocation ). ×

Orphaned recipient—this is a situation where a living donor kidney allocated to a recipient in the ANZKX program is surgically removed but is unusable, damaged, lost, or unable to be implanted into the intended paired recipient, even though the co-registered living donor for that recipient has already successfully donated to the other recipient in the paired exchange. This also includes the situation in which a kidney is damaged, the damage is identified by the recipient transplant surgeon prior to implantation and the kidney fails early after transplant. New Zealand and Australia will be responsible for the subsequent allocation of a kidney to an orphaned recipient enrolled in their country. In Australia, the ‘orphaned recipient’ will receive priority listing on the transplant waiting list (Level 3 interstate exchange) for a suitable kidney from the national deceased donor organ pool. In the case of a very highly sensitised recipient (very high calculated panel reactive antibody level) who is likely to be difficult to match, the degree of prioritisation can be altered following discussion with RTAC. Given that pre-emptive recipients are not on the deceased donor wait list in OrganMatch, approval will be sought from RTAC to allow orphaned pre-emptive recipients to be made active on the transplant waiting list and receive priority allocation. In New Zealand, prioritisation for orphaned recipients is defined in the NKAS algorithm.3737 The New Zealand Kidney Allocation Scheme, National Renal Transplant Leadership Team, December 2022. (Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/about-ministry/leadership-ministry/expert-groups/national-renal-transplant-service/nrts-papers-and-reports#natioanl_kidney_allocation ). ×

These agreements have been made with the approval of the Organ and Tissue Authority, New Zealand’s NRLT Team, and RTAC endorsement. (For more information on the ANZKX, see the following link: https://donatelife.gov.au/ANZKX)

5.4.5 Unplanned (exceptional) deviations in allocation

In clinical medicine, circumstances often arise that require immediate decision-making, and it is not possible to predict all potential deviations from the usual allocation process. In every case, the overriding principle is to ensure every donated kidney is allocated to a suitable recipient and not wasted. These exceptional cases are audited and reviewed by RTAC and state-based transplant advisory committees, to ensure the principles of allocation are followed as far as possible and, if not, that the reasons for deviations are acceptable. Exceptions to usual allocation procedures often occur for the sake of patient safety, or to minimise the risk of discard of an organ. Examples of such circumstances are listed below.

Prolonged ischaemic time: if there is a prolonged cold ischaemic time, it may be particularly important to transplant the kidney as quickly as possible and therefore it may not be possible to transport the kidney interstate, as it would be deemed unusable on arrival. In these cases, the kidney needs to be allocated in the state in which it was donated, using the state-based allocation algorithm.

Technical issues: where there are technical issues that make it safer for the local surgical team who removed the deceased kidney to be involved in transplanting the organ. Examples include:

Kidneys removed from living patients as a treatment for renal cancer. A small cancer is removed, the kidney repaired, and the kidney transplanted into a recipient who often has borderline eligibility for listing, who understands the additional risks of possible cancer transmission and surgical complications.3838 Nicol DL, Preston JM, Wall DR, et al. Kidneys from patients with small renal tumours: a novel source of kidneys for transplantation. BJU Int, 2008;102(2):188–92. ×

Kidneys that have significant anatomical abnormalities of the blood vessels (e.g. an aneurysm), ureter or parenchyma (e.g. large cysts, possible tumours that require biopsy). These kidneys may also pose an increased risk to the recipient and will generally be acceptable only to some patients on the TWL.

Intended interstate recipient is medically unfit: where the intended recipient is found to be medically unfit to undergo transplantation after the organ is shipped. For example, a kidney from Sydney may be on its way to Perth, however the intended recipient in Perth is found to be medically unsuitable due to a previously unrecognised problem. In order to prevent discard of this kidney, it may be necessary to reallocate the kidney to another patient located in Perth, rather than attempting to ship the kidney interstate a second time. In this example, the “urgency” of need for the next patient on the allocation list as well as the feasibility of getting the kidney to that patient should be considered.

No blood group/ immunological compatible recipient: for example where the donor is blood group AB and there is no one on the TWL of that blood group who is also HLA-compatible. In order to promote organ utilisation, transplanting units and/or donor coordinators may explore the following possible recipients: (i) an AB patient on dialysis that is not yet active in OrganMatch TWL but is deemed suitable to receive the organ (this is usually someone about to be made active within OrganMatch who has met all the requirements for listing including tissue typing); or (ii) someone who is close to needing dialysis but has not yet commenced and is deemed suitable to receive the organ, or (iii) someone with an incompatible blood group who may be able to receive the organ with additional treatment (such as plasma exchange).

5.4.6 Allocation of living donor kidneys to patients waitlisted for a deceased donor kidney

In very rare cases, when a kidney is required to be removed from an otherwise healthy individual with a kidney- specific disorder (e.g., a small tumour), the patient may indicate a wish to donate that kidney to someone awaiting kidney transplantation. Such kidneys can be repaired and offered to patients on the deceased donor waiting list according to the state-based allocation algorithm. Patients who are offered this type of kidney should be informed, counselled, and consent to the risks and benefits of receiving this organ before transplantation proceeds.

Non-directed altruistic donors (NDAD) are living donors who come forward wishing to donate a kidney but without an identified recipient. NDAD are fully assessed medically, surgically and psychologically as per standard protocols.

In Australia, if they are deemed suitable their donated kidney will be allocated according to the policy of the relevant state transplant advisory committee. This is usually done through the ANZKX program, and a chain of transplants will be performed with a donor kidney remaining at the end of the chain. This kidney is then allocated by OrganMatch to an Australian recipient on the deceased donor TWL as per ANZKX guidelines. This recipient on the TWL should be within the state of the NDAD if possible.

In New Zealand, the NRLT Team encourages units to consider entering suitable NDAD into the ANZKX. If NDAD donate directly, they are allocated according to the NKAS. If NDAD donate into the kidney exchange, the kidney at the end of the chain is allocated as a NDAD within the NKAS.3737 The New Zealand Kidney Allocation Scheme, National Renal Transplant Leadership Team, December 2022. (Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/about-ministry/leadership-ministry/expert-groups/national-renal-transplant-service/nrts-papers-and-reports#natioanl_kidney_allocation ). ×

5.5 Allocation: New Zealand

All deceased donor kidneys are allocated on a New Zealand-wide basis.

Kidneys must be offered to recipients according to the rules specified under the New Zealand Kidney Allocation Scheme37. For details, visit:37 The New Zealand Kidney Allocation Scheme, National Renal Transplant Leadership Team, December 2022. (Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/about-ministry/leadership-ministry/expert-groups/national-renal-transplant-service/nrts-papers-and-reports#natioanl_kidney_allocation ). ×

5.6 Multi-organ transplantation

Uncommonly, a patient may require a multi-organ transplant, for example a liver and a kidney or a heart and a kidney at the same time. If, after detailed assessment by the treating specialists, a patient is deemed suitable, a request for consideration of a multi-organ transplant is jointly submitted to the local/state advisory committees. Each request is considered on a case-by-case basis.

Some patients may be considered for multi-organ transplantation prior to reaching kidney failure but will have significantly reduced kidney function to warrant a combined transplant.

The allocation of kidneys in the context of multi-organ transplantation follows different rules to standard allocation. For example, in the case of a patient deemed suitable for combined liver-kidney transplantation, when a liver is allocated to this patient the kidney from the same donor will be simultaneously offered. Whilst there is no confirmed process for multi-organ listing, it is currently under review by TSANZ.

In New Zealand, if the non-kidney transplant team consider that their patient also needs a kidney transplant, then a request is made and assessed by a kidney transplant physician at Auckland Transplant Centre. If the Auckland transplant group agrees to the multi-organ transplant, then the patient will be listed for multi-organ transplantation including a kidney.

5.7 Emerging Issues

The next review of the Australian Kidney Allocation protocol has now commenced and will build on further developing a more graded allocation algorithm, to ensure ongoing improvements in balancing utility and equity of organ allocation and kidney transplant outcomes.